U.S Army Military Vehicle Painting During the Gulf War

In 1990, the majority of Army vehicles that arrived in the Gulf were wearing their NATO 3-color camouflage patterns. They stood out against the desert sand. A lot of vehicles needed to be repainted–and quickly.

On August 2, 1990, the Iraqi army began its invasion and occupation of Kuwait. A multi-national coalition formed in response, and troops poured into the region, leading to operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. This buildup resulted in the eventual deployment of some 697,000 U.S. military personnel to the region.

As part of this deployment, the United States shipped thousands of vehicles to the Persian Gulf area. The vast majority of these vehicles arrived in theater wearing their NATO 3-color camouflage patterns, that, needless to say, made them stand out against the desert sand that dominated the operational area. A lot of vehicles needed to be repainted—and quickly.

The Anniston Ad Dammam Site

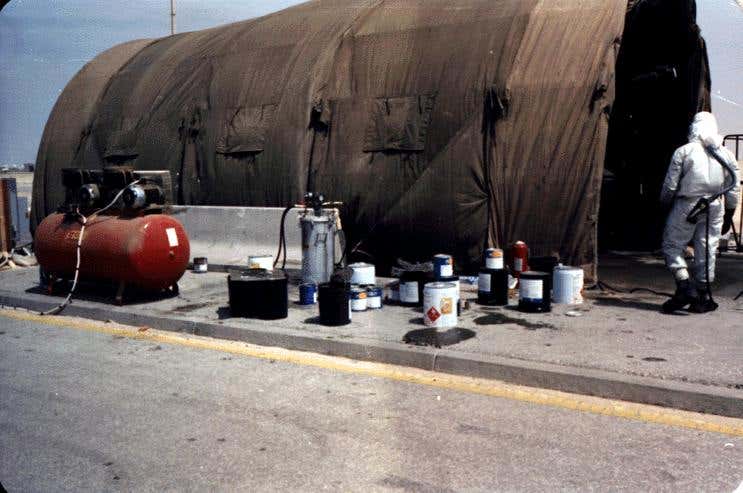

The first in-theater painting operation was set up in the Saudi Arabian port of Ad Dammam in September 1990. The site was initially established and run by civilians from Alabama’s Anniston Army Depot. The members of this group were trained and experienced in the application of CARC and arrived fully equipped with their own protective equipment, including protective suits and air purifying respirators. In February 1991, painting activities at this facility were turned over to members of the 900th Maintenance Company of the Alabama National Guard.

Ad Dammam and Al Jubayl

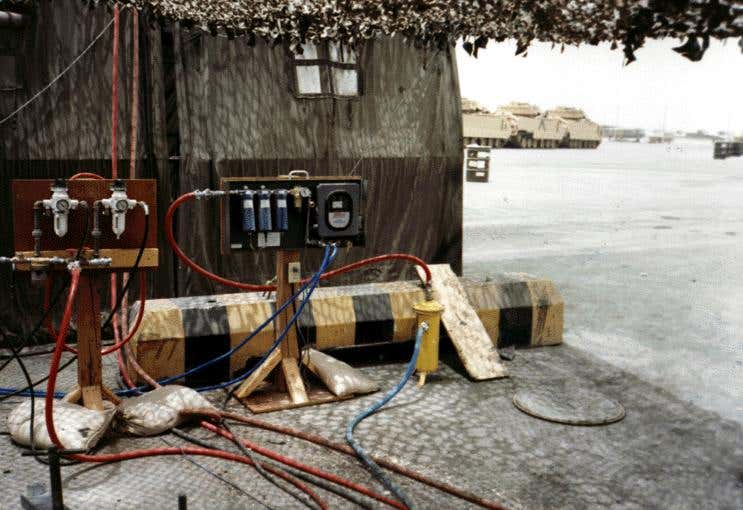

In December 1990, the Army Materiel Command (AMC) established two new major CARC spray-painting operations in Saudi Arabia, one in Ad Dammam (separate from the Anniston site) and the second in the Port of AL Jubayl. The 325th Maintenance Company of the Florida National Guard ran both of these sites.

Members of the 325th arrived in theater with no training or experience in CARC application, nor did they have any protective equipment. By the time they ceased operations in February 1991, these two sites had painted over 8,500 vehicles and other equipment.

The sites operated by the 325th became the focus of investigation both during and after the war when numerous health complaints began coming from veterans of this unit. For the sake of this article, the intent is not to debate the link between CARC and Gulf War Syndrome. Nevertheless, the interviews conducted by the Department of Defense provide great insight as to how painting was done. The following points recur in many of the interviews.

·Painters worked 12-hour shifts

·Crews consisted of a team of three: painter, mixer, and a hose handler

·Crews were given locally procured paper masks which clogged quickly

·Painters were given disposable paint suits, which tore often

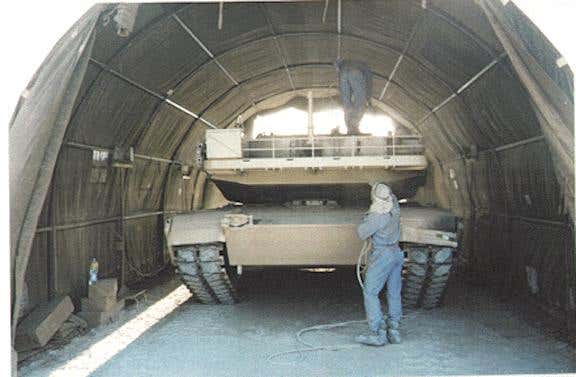

·Painting was done in large open-ended tents

·Paint prep was limited to washing the vehicle with water

·Painters were given no background on CARC. Most noticed the warning labels on the cans

·Personnel complained of headaches, dizziness and frequent nosebleeds.

There were cases where units arriving in theater had to paint or assist in painting their own vehicles. Through interviews with veterans of the 2nd and 3rd ACR, I have learned the following.

The 2nd ACR disembarked its heavy equipment at the port of Jubayl, where they established a “tent city” several miles outside the port. Combat and combat support equipment were placed in long lines and, as a 2nd ACR veteran put it, “a bunch of guys with paint guns and the little paper paint masks would start spraying, nothing scientific about it.”

A mixture of support units and civilian contractors supplemented by soldiers from the unit whose vehicles were being painted did most of the painting. Some painting was done in open-ended tents; the vehicle was pulled in, painted, allowed to “tack” for about 20 minutes, and then driven to the unit’s holding area to dry completely.

The vehicle crews were responsible for pre-paint prep and masking of their own vehicles and the quality of the prep and masking depended on the individual crew’s motivation and the availability of supplies. In some cases, surface preparation was limited to hosing off the vehicle with water. Some crews recall being given a reddish colored soap with which to wash their vehicles. Masking was done with whatever tape was available and the old soldier’s standby, grease. Many vehicles ended up with vision blocks that were painted shut and crew members could not get the CARC off the glass without damaging the lenses. Many vision blocks had to be replaced, creating shortages in the Army supply system.

It seems that the lack of experience in mixing and applying CARC led to some color issues, several veterans have told me of a batch of 5-ton trucks that came back with what they described as a “pinkish tint.”

There were vehicles that for one reason or another were not painted when they arrived in country. These were painted later by the units, most with brush-on CARC, but it seems that some crews in the 84th Eng. Co. were given spray cans of tan paint to use; this could not have been CARC since CARC was not available in spray can form at that time.

The story is much the same with the 3rd ACR. One veteran told me that they ran out of CARC and began to use a locally procured paint that looked more white than tan. I have found no other evidence to support this.

Which Vehicles Were Painted

It was determined early on that only a limited number of vehicles would initially be repainted in tan; there were a number of factors controlling this decision:

1. They did not want the build-up of combat power in the region to be slowed by painting operations.

2. There was no way that the paint application capability of AMC could be increased enough to allow all of the vehicles entering the theater to be painted in a timely manner.

3. The existing supplies of CARC were limited.

The potential shortage of CARC was the key issue to AMC. The commanders of VII Corps considered two options. The first was to paint the vehicles as they arrived and hope more CARC would be shipped before they ran out, the second option was to paint only priority vehicles in order to conserve CARC until more became available. The second option was chosen.

Priority was thus given to apply tan paint to combat vehicles like the M1 tank and Bradley fighting vehicle, engineer breaching equipment, and command and control vehicles like the M577. Increasing deliveries of CARC later allowed almost all the tracked vehicles to be painted, and eventually local commanders were given leeway to select other vehicles to be painted.

Camouflage in the Gulf

AR 750-1 spelled out that vehicles operating in a desert environment were to be painted in overall tan, but it would seem that when the Gulf War began some people in the army began to think about camouflage.

In true Cavalry tradition, 2nd Squadron, 4th Cavalry (24th ID) decided to be different by painting their vehicles in a 3-color camouflage pattern. It consisted of wide vertical bands of tan 686 and (33446) and dark sandstone (33510) separated by thin black lines. A number of these vehicles were photographed on December 19, 1990, during a training exercise.

Coalition Vehicle Markings

The coalition forces in the Gulf adopted a system of geometric markings using V’s, chevrons, lines, dots and dashes. Markings meant different things in different formations and the major area commander determined meaning.

Vehicle names were always an important way of identifying individual vehicles in a formation, but the new tan color made the names easier to see and brought them to the public’s attention. I recall a vehicle named Damn Yankee getting the attention of rocker Ted Nugent who had a band of the same name at the time. The naming of vehicles followed the tradition where the first letter of the name would be the letter of the company; thus, the aforementioned vehicle would have been from “D” company.

The Gulf War also saw a comeback for vehicle art, although specifically prohibited by AR 750-1 cartoons and characters can be found in several photos of Army vehicles, some even a bit on the risqué side. One must note that aircraft nose art made a comeback as well at this time and attempts were made to enforce the regulations and have the art removed, but troop morale and esprit de corps won out in most cases and the markings stayed, at least until the shooting stopped.

The use of unit markings was also haphazard during the early stages of the conflict. Due to the enormous media coverage, many vehicles had unit marks covered or completely removed; this appears to hold especially true in combat units. Photographs of vehicles in the Gulf show that in some units, tactical markings were applied very neatly, while other units had very crude markings applied.

All markings on CARC painted vehicles were supposed to be applied using decals or CARC paint. Several veterans have informed me that they were given black “rattle can” spray paint with which to apply tactical and unit markings and as mentioned earlier, CARC did not come in spray can form.

Conclusion: Gulf War Transformed the Military

Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm saw the U.S. Army forced into making a rapid transition from a European battle to a desert combat scenario, and the coloring of vehicles and gear was one of the most obvious changes to even the most untrained observer. The need to rapidly change the color of a large part of the fleet was hampered by the hazmat aspects of CARC paint, and highlighted the need to develop and train additional forward deployable painting operations.

Lessons from ODS also led to the reformulation of the CARC tan color paint to increase the UV reflective properties of the paint in an attempt to keep the vehicles cooler.

Post operation investigations into CARC related health issues, particularly with veterans of the 325th Maintenance Company of the Florida National Guard, led to major changes in pre- and post-deployment health screening of troops and spurred the army to seek a less carcinogenic alternative to CARC. By 2000, a waterborne version of CARC was finding its way onto army vehicles.

RELATED:

*As an Amazon Associate, Military Trader / Military Vehicles earns from qualifying purchases.

Chris Causley is a founding member and current president of the Michigan Military Technical & Historical Society in Eastpointe, Michigan. A long-time collector, historian, and vehicle restorer, he has narrowed his focus to capture and preserve the story of Michigan’s contributions to the defense of the nation from 1900 through today.