Clearing the air

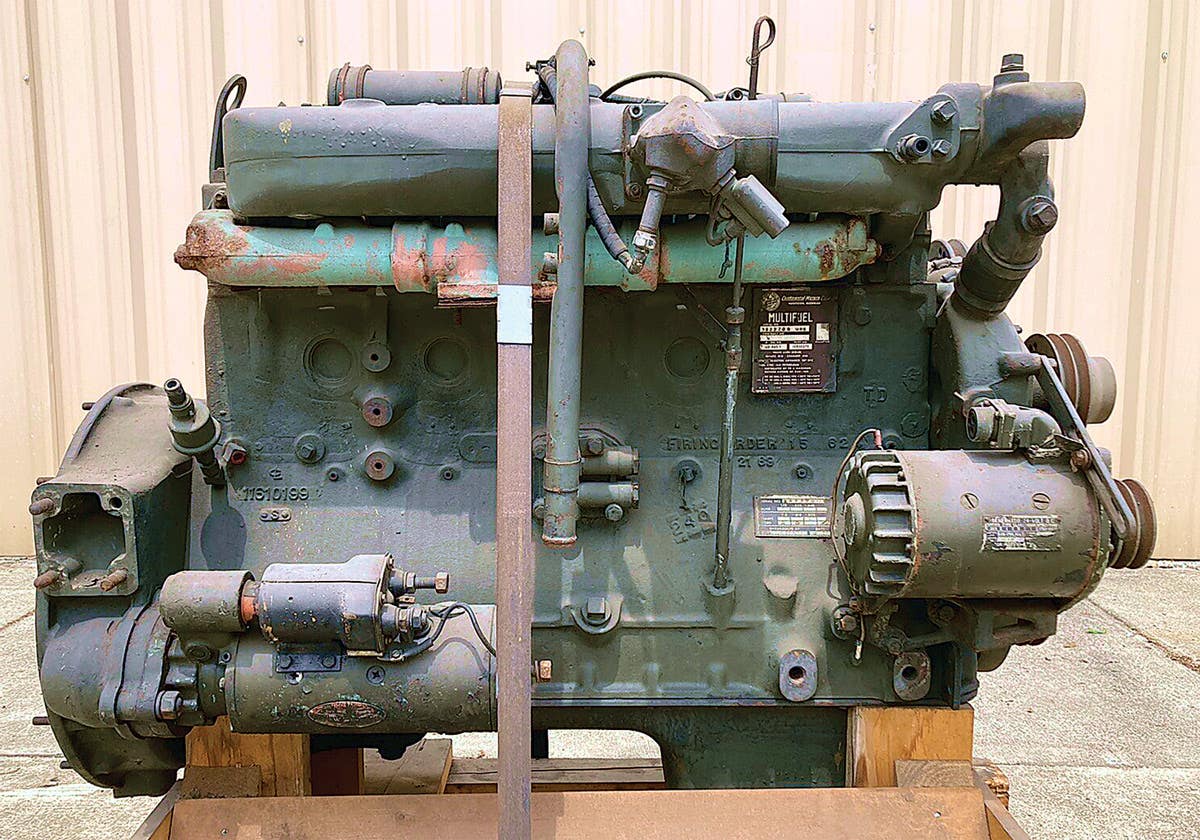

Servicing historic military vehicle air cleaners

Some historic military vehicle service and maintenance tasks are so mundane, boring or dirty that we sometimes just put them off. Common examples are lube jobs, checking and/or changing the gear oil in transmissions, transfer cases and axles, and draining, flushing, and renewing the engine coolant and brake fluid. Ironically, it’s often the dirty, boring, and relatively simple maintenance duties that do a lot to keep our vehicles on the road, in good mechanical condition, and ensure that they have a long and dependable life. At the top of many don’t-wanna-do lists is servicing a vehicle’s air cleaner.

Back in the early days of Military Vehicles Magazine I started the question-and-answer “Tech Tips” column, and one of the first letters I received was about an oil-bath air cleaner on an M38. The question was: “Where does the extra oil come from to raise the level in the oil cup from Normal to Service?” My answer was (and is) that the oil level doesn’t rise because extra oil mysteriously appears, but rather because of dirt and dust particles – sediment -- collected by the air cleaner, which settle to the bottom of the oil cup.

Answering this and other questions about air cleaners (or air filters, if you prefer) is what this article is about. In past articles I’ve mentioned various vehicular components that seem shrouded in mystery in regard to how they work or what their useful purpose might be. I’ve also written about components that seem so long-lived and trouble-free that their service is often overlooked until they finally wear out and fail. Wheel bearings and universal joints are two examples. But, after sixty-some years experience, I would have to say that the most universally-neglected and least-serviced component of many vehicles are their air cleaners. In fact, I would bet that the air-cleaners on about 80 percent of the world’s vehicles need servicing at this very moment, and probably also a few simple and inexpensive repairs, because they’re dirty and/or otherwise not functioning properly.

One of the major differences between components such as universal joints and air cleaners is that when a universal joint fails it’s often suddenly and may leave one stranded somewhere, whereas even total failure of an air cleaner -- such as being so clogged with dirt that an engine won’t run -- is seldom a sudden occurrence. Basically, when an air-cleaner fails, an engine only wears out faster. This wear is accelerated if a vehicle is being used in dusty or dirty environments.

I was once doing a demolition job in Central California, operating an ancient Allis-Chalmers bulldozer with a 6-71 GM diesel engine. It was August, the dust was as fine as talcum powder and billowed around in a blinding blizzard as the ’dozer’s tracks churned it up. The engine was fitted with a pair of oil-bath air cleaners, and I had to clean and service them at least three times a day. I could actually feel the gradual loss of power as they clogged up with dust. I could also see the engine begin to produce black smoke from too rich a fuel mix as it struggled to breathe. Of course most HMV owners won’t encounter a situation this extreme, but a day spent driving in dusty off-road conditions with will usually necessitate air cleaner service. At the very least, and even if one never takes their vehicle off pavement, a dirty air cleaner is wasting fuel and causing needless wear in the engine.

How?

Since the engine is not getting enough air, there is an excess of fuel and incomplete combustion, which washes lubricating oil from cylinder walls and dilutes the oil in the crankcase. On the other hand, an air cleaner with a damaged case that doesn’t seal properly, a rusted case with pinholes, or loose, leaky, or deteriorated hoses, fittings or gaskets, is also causing unnecessary wear by letting the engine suck in particles of dust and grit. These not only muddy up the oil, but dust and grit mixed with oil makes a very efficient polishing compound, which will polish things inside an engine that shouldn’t be polished any more than they already are.

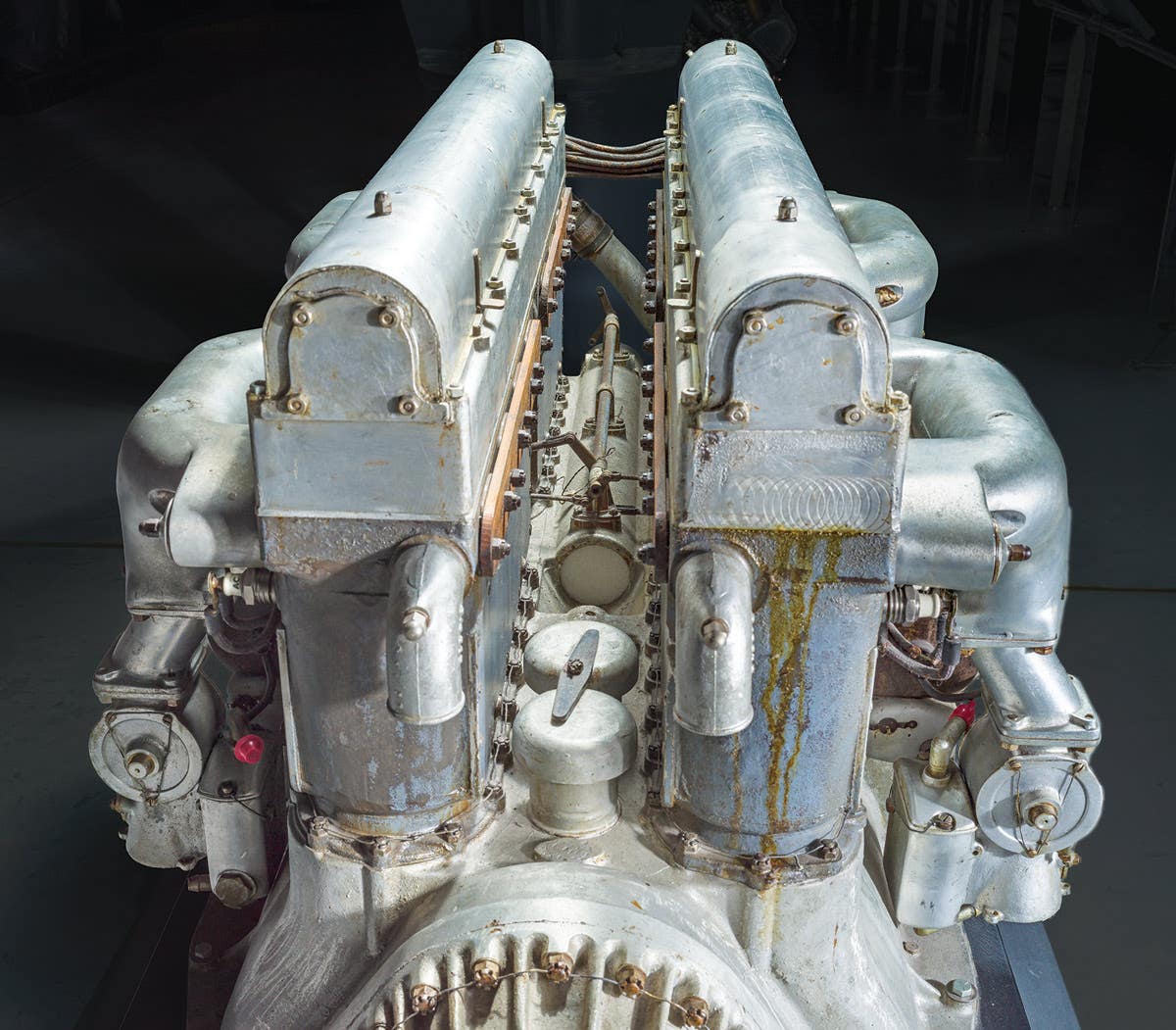

There are many sizes, shapes and styles of vehicle air cleaners. Some mount directly to an engine’s carburetor or intake manifold, while others are located elsewhere within the engine compartment or out on a vehicle’s fender or cowl. However, there are actually only two basic types of air cleaner: oil bath, and dry (or replaceable element). Some heavy equipment such as mine trucks or bulldozers may have air cleaners that are combinations of both types; and there are also pre-cleaners, which are commonly used on newer 2-1/2-ton and larger military trucks.

Positive Crankcase Ventilation (PCV) systems and their components are included in this article, because the care and service of these are often essential to the efficient operation of an air cleaner. Many crankcase breathers are miniature air cleaners all by themselves and require the same service and attention as the main unit. In addition, most of the components of a deep water fording system are either part of, or an extension of, a PCV system; and since many common M-series military vehicles, such as the M38, M38A1, M151, M37, M715, M35, are fitted with these systems -- whether or not a deep water fording kit is installed -- one should be aware that their many hoses, tubes, fittings, gaskets and connections provide performance-robbing or potentially engine-damaging air or vacuum leaks.

One may ask, of the two basic types of air cleaners, which is better, oil bath or dry? Generally speaking, a dry type is the most efficient at filtering out dust and grit… but only if properly serviced and maintained. The main problem with dry type air cleaners is that the owners of vehicles so-equipped often try to save money, either by not replacing the filter elements when they need replacement, or by trying to clean, and sometimes damaging them so they leak and let dirty air into the engine. Personally, I prefer oil bath air cleaners, since the only expense is a pint or two of new oil, plus the time it takes to service the unit.

How often should an air cleaner be serviced? A smart HMV owner will of course consult their vehicle’s manual for normal service intervals, but will usually also find an advisory to, “Service more often or daily under severe operating conditions.” Such instructions may also be on a tag or decal on the air cleaner unit. However, use common sense, taking into account how frequently you drive your vehicle and under what conditions to judge when you should inspect and service the air cleaner. At the very least, get into the habit of checking your air cleaner half as often as you check your vehicle’s water and oil… especially if you drive in a dusty environment.

For most common HMVs with oil bath air cleaners, checking the air cleaner is often as simple as unscrewing a wingnut or loosening a clamp. We’ll get to the servicing process later, but for an inspection all it usually takes is a peep into the oil cup or reservoir to make sure the level is at the “safe” or “normal” line and the oil is still fairly clean, not black or muddy. You can also dip a finger into the oil cup to feel if there’s a layer of sediment in the bottom.

It’s often even simpler to check dry type air cleaners… just take out the element to see if it looks dirty. (It was probably white when new.) Tap it gently to see if dust falls out. An old shade-tree test was to hold the element up to the sun to see if light came through: if it did, then supposedly the element was still okay… though this method is not very accurate.

On the other hand, sometimes a clean oil reservoir or a spotless dry type element can indicate that an air cleaner isn’t working properly, or there is a leak somewhere in the air intake system. For example, if you drive a lot where it’s dusty, and yet after repeated inspections you keep finding that the oil in the cup is clean and there’s never any sediment in the bottom, or your dry type element never seems to get dirty, it’s time to suspect an air leak.

It might be helpful at this point to understand how the two basic types of air cleaners work. The smaller, light-duty dry types are the simplest; the element strains all the air before it enters the engine like a coffee filter strains the grounds out of coffee. The element catches and traps dust and grit particles down to a certain specified size, which is usually stated in microns. Naturally, the smaller the particles the element can trap, the more efficient it is in protecting an engine from wear. The downside is, since engines require large amounts of air to run, a small air cleaner can’t filter as finely and still provide enough air. Therefore, when it comes to air cleaners, bigger is usually better.

Up until around the mid-1920s, many cars and trucks either didn’t have factory air cleaners -- though there were various aftermarket accessories -- or they had some sort of wire mesh screen that kept rocks and small animals out of the engine. While this was pretty rough on engines, especially considering that most roads weren’t paved in those days, the engines were loose and primitive in regard to tolerances and materials and were not very long-lived anyhow.

As an air cleaner’s filter element clogs up with trapped dirt particles, less and less air gets through to the engine. Fuel mileage begins to suffer, and lubricating oil is washed off cylinder walls by excess fuel. One can often save a little money and extend replacement intervals by gently tapping the accumulated dust out of a dry type filter, or gently blowing it out from the inside with low pressure air. Be careful not to bend or distort the element or it won’t seal inside the air cleaner’s case. Most light-duty dry type filter elements should not be washed. And, unless the manufacturer recommends it, never try to make a dry type element “more efficient” by oiling it. While there are some dry type aftermarket air cleaners that do require oiling, that will be specified. Oiling any other dry type element will only reduce the air flow as if the element was dirty.

Of course, the manufacturers of dry type filters want you buy a new element every time it gets dirty, so most elements aren’t meant to be cleaned, nor will they endure many cleanings. They are also not meant to last a long time, and the rubber or vinyl will shrink so the element won’t seal inside the air cleaner’s case. An aged element that stays clean after repeated inspections has probably shrunk -- assuming there is no leak in the air intake system -- though one could resort to temporarily padding it with weather-stripping if a replacement can’t found right away. And, when trying to clean and reuse an element, one reaches a point of diminishing returns where a few dollars saved now may end up costing a lot more on engine repairs in the future. Be aware that even though an air cleaner may be in perfect condition and fully functional, it can’t do its job if there are air leaks somewhere else, such as loose mountings, clamps, fittings, or deteriorated hoses and gaskets.

The simplest dry type air cleaners mount directly to the top of an engine’s carburetor or intake manifold. Assuming the air cleaner’s case isn’t bent, damaged, or rusted with holes, and the filter element is in good condition and sealing properly -- and is also the correct element for that unit -- the most likely place for an air leak is the gasket where the filter case meets the carburetor or intake manifold. A shriveled or missing gasket will let dirty air into an engine, especially if the filter element itself is dirty. Air will take the path of least resistance, and would rather enter the engine through a leak than go to the bother of being filtered. It’s simple to make a new gasket from gasket paper; and smearing the gasket with wheel bearing grease will provide a better seal. Dirty air can also get in through the hole on top of a filter case -- usually where the wingnut goes to hold the top of the filter in place – but a rubber washer will solve that problem. If your vehicle’s air cleaner has extra fittings or hoses -- such as for a PCV or fording system -- make sure they’re firmly fastened and sealed. You should also check to be sure the hoses are in good shape and not rotted or cracked.

Oil bath air cleaners work on a different principle from most light-duty dry types. While oil bath air cleaners usually have an element of steel wool, or what may look like Excelsior or seat-cushion stuffing, this element is often not removable from the filter case. This material is actually the second-stage, or final scrubbing, of the air cleaning process in an oil bath unit. Most of the actual air cleaning takes place when the air flow momentarily slows and reverses direction above the oil in the reservoir or cup. Air is sucked in and down from the top of the filter case. It is then drawn horizontally across the surface of the oil, where it slows a little. As it slows, most of the larger and heavier particles of dirt and grit fall into the oil. Then the air is pulled up toward the wire wool (or stuffing) and more dirt particles fall back into the oil. Finally, the smallest and lightest particles are caught and trapped in the oily wool (or stuffing) before they can get into the engine. This is why it’s important to thoroughly wash the element whenever one services an oil bath air cleaner. Many people are not aware that simply cleaning the oil cup and adding new oil is only doing part the job. And, because it’s a messy job, some people put it off too long.

As dirt particles sink to the bottom of the oil cup, the oil level rises, which sometimes mystifies people -- as mentioned at the beginning of this article -- or confuses them into thinking that more oil is somehow being pulled in from the engine. From my own experience on everything from M38 jeeps to Euclid mine trucks, I would say that if you wait for the oil to reach the Service line in the cup, you’ve waited too long to service the air cleaner.

Oil is relatively cheap, and you don’t have to use the same multigrade or expensive brand in the air cleaner as you may be using in your engine. Read your manual, of course, but in most cases, except for severe cold weather operation, the cheapest 30 weight will work just as well in your oil bath air cleaner as five-dollar-a-quart synthetic. Remember that the purpose of the oil in an oil bath air cleaner is only to trap dirt particles, not to lubricate anything. Again, read your manual. It should specify what weight of oil to use at different temperatures. While most manuals do advise using the same oil in the air cleaner as in the engine, this is generally for the sake of simplicity and convenience.

The basic service procedure for most oil bath air cleaners is to wash out the cup or with solvent, and rinse out the wire wool (or stuffing) with solvent. For most smaller oil bath units, such as those that mount atop the carburetor, this is a simple task; and the entire unit can be removed from the vehicle and washed. For larger units, or on some jeeps, the steel wool or stuffing can be removed for cleaning. On other units, including some jeeps, one may have to dismount the air cleaner from the firewall, fender or cowl to wash it. Since this is a time-consuming task, a lot of people don’t do it… or don’t do it often enough. However, there is no other way to properly service such air cleaners.

The steel wool (or stuffing) should either be allowed to dry completely before reassembly, or be gently blown dry with low pressure air. It should then be squirted with fresh oil, but don’t overdo it, especially if you have a diesel engine, or the engine will suck in the oil and run rich for a few moments after startup. Likewise, if you have a diesel, and have used gasoline to wash the filter element, be very sure the element is dry before start up.

Lastly, the oil cup should be filled with fresh oil up to the Safe or Normal line. Don’t overfill it, especially on a diesel, or you’ll encounter the same situation of an over-rich air mix as mentioned above. Even a gasoline engine may smoke and run rich for from sucking in excess oil.

As with carburetor-mounted dry type air cleaners, check and maybe replace the mounting gasket and/or wing-nut washer to prevent any air leaks, and examine, tighten or replace any attached hoses or fittings. On canister-type oil bath units, check the seal where the oil cup joins the main body. Also make sure the clamps or sealing ring hold the cup tightly in place, because an air leak here is a serious problem, messing up the air flow so the unit can’t do its job.

Many large dry type air cleaners use the same reverse-direction principle as the oil bath types in addition to replaceable filter elements. In these units, the larger and heavier particles of dust and grit fall to the bottom of a dust cup or collector before the air is filtered by the element. Naturally, one has to check and clean out the cup at regular intervals. Keeping the cup clean is more important for a dry type unit because there is no oil to hold the sediment, though some heavy-duty dry type units do have an oil reservoir. Service for these is common sense…one checks the dry element for dirt and condition, cleans or replaces it if necessary, then and cleans and refills the oil cup just like an oil bath unit.

No matter what type or size of air cleaner your vehicle has, check the case for damage, distortion, or rust holes, and replace all questionable gaskets and seals. The same goes for any attached hoses and fittings. Some super-duty air cleaners have pre-cleaner devices. These are usually at the top of the case, and catch rocks and small animals before air enters the main unit. Pre-cleaners may operate on the reverse-direction principle. Again, always read your vehicle’s manual, but the servicing procedures for pre-cleaners are usually obvious.

On many diesel or multifuel-powered 2-1/2 ton and larger military trucks there is a service or restriction indicator. These devices are supposed to pop a red flag to warn when the filter element is dirty and needs to be replaced or cleaned. They work on vacuum -- as the air filter gets dirty, the engine has to suck harder -- but I’ve found most of these gadgets aren’t very dependable. Many give false alarms; some don’t work at all; and just as when waiting for the oil in your air cleaner’s cup to reach the Service level, if you wait for one of these things to go off you’ve probably waited too long.

At this point we have inspected, serviced and/or repaired our air cleaner units, and hopefully fixed any leaks in their cases, fittings, hoses or tubes. Let’s move on to inspect, service, and possibly repair the other components of our engine’s air intake system. As mentioned earlier, some engines have a separate crankcase breather. This may be a mushroom-shaped cap, often where you pour in the engine oil, or it might be a can-like thing packed with “stuffing.” You should thoroughly wash out the stuffing with solvent, squirt it with fresh oil, and reinstall the unit on the engine. Naturally, you’ll also inspect any attached hoses, fittings or connections, and replace any questionable gaskets or seals. Even if your engine just has a simple tin cap to add oil, the cap should have a gasket or dirty air will be sucked into the engine. Check the condition of this gasket, replace it or make a new one if it’s damaged or shriveled. Smearing it lightly with wheel bearing grease will provide a better seal. Some engines may have a miniature oil bath or dry type air cleaner for a breather; and the service and/or repair of these is the same as for the main unit.

Before we go any further, it would be wise to check what should be an obvious place for an air leak, yet a place that is often overlooked when trying to track down such leaks. This is the engine’s intake manifold, and the gaskets where it attaches to the engine block. If your engine never seems to idle quite right no matter how many times you’ve tuned it up and/or replaced or rebuilt the carburetor, and/or stutters or stumbles during acceleration, you should suspect an air leak in or around the intake manifold. Check other obvious places for leaks, such as the carburetor-to-intake manifold gasket, and the carburetor itself for any shrunken or leaky gaskets or even a missing plug. Don’t forget the throttle valve butterfly shaft, because the bushings are often worn on vintage vehicles and will leak a lot of air. Many “professionally rebuilt” carburetors come out of their boxes with worn out butterfly bushings that were never replaced. Waterproof M-series carburetors usually have seals on the butterfly shaft, but these may leak due to age.

Check all the vacuum lines, hoses and fittings that go to the windshield wipers, as well as the wiper motors themselves for leakage. Old vacuum wiper motors often leak at the switch valve, usually accompanied by a slight hissing sound. While you don’t have to worry about much dirty air getting into your engine through tiny leaks such as these, your engine will probably never idle quite right.

Other related areas to check are the vacuum side of a double-acting fuel pump and its hoses, tubes and fittings, as well as the vacuum line to the distributor, if equipped with a vacuum-advance. Also check the vacuum-advance mechanism itself: the diaphragm ages, fatigues, and may leak, which will also mess up the spark-timing. Try sucking on the vacuum advance hose or tube, or use a vacuum pump, to see if the mechanism leaks or if it’s actually working. Most distributors have a mechanical advance in addition to a vacuum advance, and you would not be the first person in the world to discover that you’ve been driving for years with no vacuum advance.

Do a visual examination of your engine’s air intake manifold for cracks, or loose or missing fittings. Just as with a vacuum advance, you would not be the first person to discover you’ve been driving with a loose manifold (where it attaches to the engine). It’s a good idea to check both the air intake and exhaust manifold mounting bolts occasionally, and tighten them if necessary. If you have an M715, be aware that its aluminum intake manifold is fairly delicate and is easy to distort or crack by over-tightening the mounting bolts.

Intake and exhaust manifold-to-engine-block gaskets don’t last forever; and while replacing them is not especially fun, it’s usually neither complicated or expensive. If you have a GMC 270 or 302 engine (CCKW, DUKW, M211, etc.) or a Chevy 235 engine (G-506) pay attention to the locating rings that fit between the intake manifold and the engine block. These little rings are important. Over the years, after many owners, and after many engine rebuilds or repairs, these rings are often lost or discarded. They are also easy to bend or crush. Without them it’s difficult to properly install the intake/exhaust manifold assembly so it doesn’t leak. Furthermore, the assembly may shift over time and begin to leak without these rings. You can make satisfactory replacements by cutting stainless steel hose clamps, but pay attention to size if you have to fabricate them… if you make them too wide you may crack the manifold when installing it. (This advice also applies to civilian G.M.C. 228, 236 and 248 engines.) If you suspect a leaky intake manifold gasket, and you’ve already tried tightening the bolts, a simple way to check is to squirt engine oil around the gasket with the engine idling. If the idle picks up a bit or smooths out, the gasket is leaking.

Lastly, we come to the components of the positive crankcase ventilation system, which may be as simple as a PCV valve and a single short section of tubing (as on most WWII jeeps) or a complicated maze of small tubes, hoses, connections, fittings and valves such as used on a waterproof M-series vehicle like an M37 or M35. For a WWII jeep, about all you need to do is occasionally check to make sure the connections are tight, and remove, disassemble and clean the PCV valve about once a year. For M-series vehicles with waterproof engines, you will have to read your manual and trace and inspect every hose, tube, and connection from the distributor down to the transfer case and fuel tank, and tighten or replace things as needed to seal up your air intake system.

Hopefully, we have covered just about everything you may have wanted to know about air cleaners. At the very least you should now know where that “extra oil” comes from.