Remembering ‘Big Bill’

William S. Knudsen was probably America’s most misunderstood, least known and arguably most important general.

It is often said that during WWII, the United States was the Arsenal of Democracy. The nation, thankfully removed from aerial attack and combat in the streets, and blessed with abundant resources and industry geared toward mass production, certainly lived up to the moniker. However, before the gears of industry can begin to churn out armaments, the decision has to be made what was going to be made, and by who. Reaching these decisions were not always linear processes.

“Big Bill” Knudsen, more formally William S. Knudsen, had come to America from Denmark as a 21-year-old in 1900. A bicycle mechanic in Denmark, once in the U.S. he worked in shipyards and then the shop of the Erie Railroad until gaining employment with the John R. Keim Mills of Buffalo, N.Y. in 1902. Keim manufactured bicycles, and when that market was slow, also produced metal components for other manufacturers. One of those was Ford Motor Co. By 1908, Knudsen was superintendent of the Keim plant, which was making Model T mufflers, fuel tanks and axle housings.

In January 1911, Ford purchased Keim, and in 1913 relocated much of the plant and 62 key men to Highland Park, Mich. One of the men hired was Knudsen, who remained in Buffalo with his new wife Clara.

Knudsen’s new job with Ford did not require him to live in the Detroit area, as he was charged with establishing 14 additional Ford assembly plants in the U.S., as well as three in Europe. He worked with Albert Kahn, and together the two men revolutionized plant design by planning the work flow first, and then creating a structure to house it, rather than the previous convention of adapting the work flow to fit the building.

By 1914, Knudsen had become a U.S. citizen, and along with is family had relocated to the Detroit area, where beginning in 1915 he oversaw all Ford branch assembly plants, as well as the Highland Park plant. At that time he was earning $25,000 per year plus a 15% bonus.

In 1919, following a confrontation with Charles Sorensen, then the No. 2 man in Ford manufacturing operations, Knudsen began to see his directives overruled by Henry Ford, in favor of Sorensen. Knudsen left Ford on April 1, 1921.

On February 12, 1922 Knudsen went to work for General Motors. During the interview, GM Vice-President Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. asked Knudsen, “How much shall we pay you?” Knudsen gave the stunning reply, “Anything you like. I am not here to set a figure. I seek an opportunity.”

Knudsen was hired at $30,000 annually, but within three weeks, Pierre. S. du Pont, GM president, promoted Knudsen to VP of Chevrolet at $50,000 per year. On Jan. 15, 1924, Knudsen moved up to vice president and director of General Motors itself, as well as president and general manager of Chevrolet. In 1933, he rose again to executive vice president of GM, and oversaw all vehicle operations in the US and Canada. Chevrolet by itself had overtaken that of Ford, with Chevy production rising from 75,700 in 1921 to 1,001,680 in 1927.

Yet another promotion came in 1937, when Knudsen replaced Sloan as president of General Motors, with a salary of more than $500,000 per year. By 1940, General Motors was firmly dug in as the nation’s biggest automaker, and arguably the largest corporation.

As war drew increasingly inevitable, on May 28, 1940, President Roosevelt had asked Knudsen to be one of seven men on the National Defense Advisory Commission (NDAC), with Knudsen serving as Commissioner of Industrial Production – at a pay rate of $1 annually. Despite Sloan, who was staunchly anti-Roosevelt, warning that he would not be able to return to GM, Knudsen resigned his position with General Motors to take accept Roosevelt’s challenge, writing to Roosevelt on June 5, 1940:

“I trust you will permit me to express my most sincere appreciation of the honor conferred upon me by my appointment to the Council of National Defense. I realize, and feel most deeply, the responsibility which you have placed in my hands and my sincere hope that I may produce results.”

“With reference to my personal affairs, I do not wish to burden you with them except to keep you informed of my status. The Corporation has granted me a leave of absence without pay for ninety days which, under the rules, must be reconsidered after that time for an extension. If agreeable with you, and this not being inconsistent with the relations existing between the Government of the United States and the General Motors Corporation, I shall be glad to function to the best of my ability for any length of time you may want, entirely at my own expense, even if it becomes necessary for me to sever my connections with the General Motors Corporation entirely.

“Please be assured that I am most happy and grateful that you have made it possible for me to show, in a small measure, my gratitude to my country for the opportunity it has given me to acquire home, family and happiness in abundant measure.”

Some pundits have alleged that Knudsen used his position to steer contracts to his former employer, however, even modest research will show that was not the case.

Once Knudsen took his position as Commissioner of Industrial Production in 1940, the first person he called to assist him was Harold S. Vance, chairman of the board at Studebaker — hardly a move that one would make in order to steer work to GM. While Knudsen had overall control of the Commission of Industrial Production, the mobilization of plants for production of trucks was under John D. Biggers, president of glassmaker Libby-Owens-Ford. Vance was placed in charge of machine tools and heavy ordnance, arguable the most important position on the National Defense Advisory Commission, as the delivery of machine tools to the nation’s factories is what made it possible to produce the myriad of weapons and other items needed. In fact, the commission was set up such that each department was led by a business executive of impeccable credentials and paid $1 per year for their government service. Each was placed in a position that would utilize their skills, but avoid conflicts of interest.

Knudsen’s Production Division controlled contracts valued at a $500,000 or more, and was responsible for Army ordnance and aircraft among other things. Chief among his responsibilities was obtaining the fullest use of all manufacturing facilities, and when necessary, providing additional facilities. Once approved by the Production Division, the Army or Navy could then award a contract based on the usual considerations of price speed, quality, etc. By virtue of his position as Industrial Production Commissioner, Knudsen also served on the War Priorities Board.

Knudsen, would find, however, that there was too much politics involved in enforcing the Advisory Commissions findings, and in 1942 he accepted an Army commission as Lt. General, although his responsibilities remained much the same.

Shortly after taking his position with the NDAC, in remarks to the press, Knudsen said, “I’m not a polished man, but I know how to make things.” One of the things that needed to be made by the nation was tanks, and what followed illustrated Knudsen’s ability to get things made.

While the imposing (6-foot-2) Knudsen was moving up the GM ranks, across town Kaufman Thuma (K.T.) Keller was rising in the Chrysler organization. Keller had come to Chrysler from GM in 1926.

In 1929, Keller was promoted to president of the Dodge Division. On July 22, 1935, Keller was named president of the Chrysler Corporation.

Keller, who is sometimes criticized as being an autocratic leader, had a considerable tendency to think big. Among the projects he undertook was the construction of the Albert Kahn-designed Dodge truck plant at 21500 Mound Road near Warren, Mich. The plant, which was initially set up to build 5,000 trucks per week, plus spare parts equal to an additional 1,000 trucks per week, opened in 1938. This facility, erected in rural Macomb County, would produce Dodge trucks for the U.S. military in WWII and beyond.

When Knudsen took up his National Defense Advisory Commission duties in May, one of the first things he examined were the War Department’s plans on tank production. Having previously worked for the Erie Railroad, he knew full well that the proposed railway equipment manufacturing firms had the facilities to build tanks, and the equipment and experience to work with large, heavy components. He also knew that these firms were not accustomed to mass production on the scale that was to be needed by the War Department. He knew, however, that the automotive industry was well acquainted with true mass production, but lacked the facilities to build tanks in the numbers needed.

On Friday, June 7, 1940, Knudsen picked up the telephone in his Washington office and called Keller asking if Chrysler would be interested in building tanks for the government. The two men agreed to meet in Knudsen’s summer home at Grosse Ile, near Detroit on Sunday to discuss matters. At that meeting Keller expressed interest in building military tanks but admitted that no one in his organization was really knowledgeable on the subject.

Four days later, Keller, along Bernard Edwin (better known as B.E.) Hutchinson, vice president and chairman of the Chrysler Finance Committee, C.E. Bleicher, VP of the Desoto Division, Edward J. Hunt, staff master mechanic, and Nicholas Kelley, VP and general counsel descended on the massive Munitions Building at the foot of the Washington Monument, in Washington, DC.

The men were there to discuss in greater detail what the government’s requirements were, and to hopefully secure the specifications. The Chrysler delegation first met with Major General Charles Wesson, chief of ordnance, who K.T. Keller in 1965 reminisced, “...did not think an automobile company could make tanks. He gave a contract to Baldwin and American Locomotive.”

General Wesson turned the group over to Colonel Alexander G. Gillespie, who provided additional details. From E.J. Hunt’s notes, we know specifically what Gillespie outlined: That the Army was about to order 1,600 tanks. While the drawings were available for a 20-ton tank (less armament) – the M2A1 – the Army envisioned this increasing to 25 tons, less armament. The Chrysler men were told to they should make their bid based on the smaller tank, and once the new design was finalized, a supplemental contract would be issued for the changes, assuming that the Chrysler bid was accepted. Gillespie further opined that the government was actually apt to purchase 5,000 tanks, and that it would take 750 days to complete the 1,600-tank order.

The Chrysler men had hoped to see a tank in Washington, but none were available.

The next day, Hunt, along with the rest of the Chrysler Corporation Master Mechanic staff, arrived at Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois. They were accompanied by L.A. Moehring, Chrysler Corporation Comptroller, W.J. O’Neil, president of the Dodge Division, his vice-president, F.L. Lamborn, A. P. Rascall, Purchasing Agent, and Robert T. Keller. Robert, or R.T., was the son of K.T. Keller, who was on Mr. Hunt’s staff at the time of the visit, would play a significant role in Chrysler’s tank production for over a decade.

After a greeting from Colonel Ramsey, commanding officer, the group was turned over to Captain Pinkerton, who briefed the group concerning the tank manufacturing process.

The next day the men were joined by K.T. Keller and B.E. Hutchinson, who had just arrived from Washington. The group wwas given a demonstration of a light tank and toured the shop floor, where the pilot M2A1 medium tanks were being assembled.

On Thursday, most of the Chrysler men departed, except for Hunt, R.T. Keller and a few more staff who stayed to further observe the manufacturing process and to arrange to get copies of the blueprints so to prepare a bid to produce the vehicles. When this group left for Detroit later that day they left with a roll of assembly drawings and a partial set of specifications. A complete set of blueprints were being packed for shipment to Detroit. These drawings arrived at Chrysler at 5 p.m. on Monday June, 17. Immediately, 197 men set to work estimating the production cost of the vehicle.

By July 17, four and one half weeks after starting, the Herculean task of producing the estimates had been completed. The 197 men tasked with this process had worked seven days per week to accomplish this.

With this information in hand, K.T. Keller along with B. E. Hutchinson, Nicholas Kelley, and L.A. Moehring went to see W.S. Knudsen and his deputy, John David Biggers, who was on leave from his usual job as president of the Libby-Owens-Ford Company. The Chrysler men told the Defense men that they had a handle on fundamental production and equipment costs, and that “...discussions of rate of production and quantities were in order.”

Mr. Knudsen asked for an estimate on 2,000 tanks at a rate of 5 per day, working one shift, while Mr. Biggers asked for pricing on 10 tanks per day, again working one shift.

The Chrysler team, sans Kelley, next visited Major General Wesson and Colonel Burton Lewis.

Keller, following up on discussions that he and Knudsen had had previously, advocated that a dedicated Tank Arsenal be constructed, which could be used not only for the production of the currently contemplated order, but also future orders as well as experimental development of tanks.

With this information, Wesson and Lewis then asked Chrysler to submit an estimate for producing tanks, and a separate estimate to build and equip the Tank Arsenal.

Two days later K.T. Keller, along with Hutchinson, Moehring and Kelley returned to Knudsen’s office, and presented to Knudsen and Biggers two proposals. One proposal would have the tank plant amortized, becoming Chrysler’s property, and the other would have the plant a government-owned, contractor-operated facility.

Knudsen and Biggers both saw advantages to the latter arrangement, and all further discussions on plant planning centered on that plan.

On July 21, William Knudsen visited the Dodge Conant Avenue plant to inspect the tank mockup as well as to review proposed plant layouts of the Tank Arsenal. Two days later a Chrysler delegation consisting of Hutchinson, Kelley, and Hunt met with Colonels Lewis and Campbell in Washington in order to report that as expected, no suitable existing facilities for the Tank Arsenal were available in the Detroit area.

More importantly, the Chrysler men advised the officers that under standard War Department contract procedures, it would not be possible to meet the various deadlines set forth by the Army in prior discussions. It was decided to seek help from Biggers and the National Defense Advisory Commission in resolving this.

On July 26, a large meeting was held at Biggers’ office. Attending from Chrysler were K.T. Keller, along with Hutchinson, Kelley, Hunt, H.S Wells, staff plant engineer and Frederick M. Zeder, Chrysler chief engineer. On the government side were Biggers, Major General Wesson, Major General Edmund Gregory, Quartermaster General, Colonel Campbell, Brigadier General George E. Hartman and representatives of the Advocate General.

Biggers told the assembled group that a working arrangement had been arrived at between the Ordnance and Quartermaster branches which would solve the practical problems in executing an arrangement with Chrysler to build tanks, with the Quartermaster assisting in the construction of the tank plant.

On August 15, 1940, Chrysler and the Army signed a contract calling for the production of 1,000 M2A1 medium tanks, as well as buying the land, constructing the Tank Arsenal, equipping the Arsenal, and operation of the Arsenal by Chrysler.

Chrysler was to purchase the 113-acre plot between 11 and 12 Mile roads, bordered by Van Dyke Avenue on the east, and the Michigan Central tracks on the west and sell it to the government at cost. This site was 4 miles north of the massive, recently constructed Dodge Mound Road truck plant. The tanks were $33,500 each on a fixed price contract, the 700,000-square foot plant and its equipment were to be charged at cost plus a fixed fee, the latter totaling about $20 million. Chrysler would then lease the plant from the government for $1 per year for the duration of the war.

The Detroit Arsenal/Chrysler Defense Plant was the largest tank plant in the USA, and would continue to produce tanks for the U.S. and its allies up through early production of the M1 Abrams – clearly making it a worthwhile investment. The plant is but one of the numerous wartime production successes of General “Big Bill” Knudsen.

Knudsen received a distinguished service medal, and after resigning his commission on May 1, 1945, received a letter from Army Air Forces commander General H.H. “Hap” Arnold. The letter read in part, “I look back with great appreciation upon the way you handled the creation of new factories, the tooling required, and the changes necessary in the production lines. These were not easy problems.”

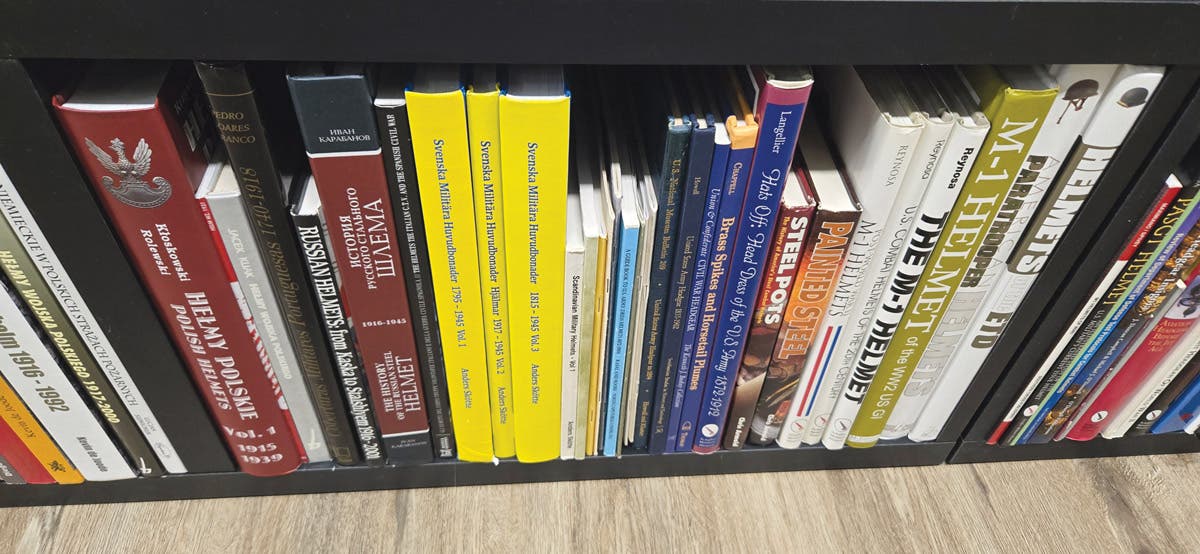

For additional information reading see M3 Lee Grant – the Design, Production and Service of the M3 Medium Tank, the Foundation of America’s Tank Industry and Studebaker US6 (including Reo Production), available from DavidDoyleBooks.com.

David Doyle's earliest published works were occasional articles in enthusiast publications aimed at the historic military vehicle restoration hobby. This was a natural outlet for a guy whose collection includes several Vietnam-era vehicles such as M62, M123A1C, M35A2, M36A2C, M292A2, M756, and an M764.

By 1999, his writing efforts grew to include regular features in leading periodicals devoted to the hobby both domestically and internationally, appearing regularly in US, English and Polish publications.

In 2003, David received his a commission to write his first book, The Standard Catalog of U.S. Military Vehicles. Since then, several outlets have published more than 100 of his works. While most of these concern historic military hardware, including aircraft and warships, his volumes on military vehicles, meticulously researched by David and his wife Denise, remain the genre for which he is most recognized. This recognition earned life-time achievement in June 2015, when he was presented Military Vehicle Preservation Association (MVPA) bestowed on him the coveted Bart Vanderveen Award in recognition of “...the individual who has contributed the most to the historic preservation of military vehicles worldwide.”

In addition to all of publishing efforts, David is the editor of the MVPA’s magazine, History in Motion, as well as serving as the organization’s Publications Director. He also maintains a retail outlet for his books online and at shows around the U.S.