Finishing the job and ending the Third Reich

Paul Eisenmann helped seal the fate of the Third Reich

Paul Eisenmann was born in the small town of Mishicot, Wis., on Feb. 22, 1922. At age 19, his work at a local furniture manufacturer was interrupted when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Following that catastrophic event, he sought a way to join in America’s call to arms. For the next few months he worked at the nearby Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company, helping to construct U.S. Navy submarines, before enlisting in the U.S. Army on Nov. 24, 1942. He reported for duty at Fort Sheridan, Ill., on Dec. 7, 1942, one year to the day after the U.S. had entered World War II.

Private Eisenmann was assigned to the 376th infantry regiment, “D” Company, a previously inactive WWI group that had been called to mobilize in June,1942, as part of the 94th division. After training at Camp Phillip, Kan., the Tennessee Maneuver area and Camp McCain, Miss., the 376th readied for their trip overseas at Camp Shanks, N.Y. On Aug. 6, 1944, Eisenmann and the others boarded the former luxury liner Queen Elizabeth, then refitted as a troop transport ship. After days of boat drills, blackouts and chow calls (taken in six shifts while being served unfamiliar British food), the men on the hot and overcrowded ship finally completed their ocean crossing on August 11, dropping anchor off the small village of Grenoch, Scotland.

Following debarkation, the troops were carried by train to the land surrounding Pinkney Park, a grand estate located one mile from Sherston, Wiltshire, England. Here they continued preparation and training in hedgerow tactics, physical conditioning and weapons. On Sept. 6, the troops again traveled by British trains, then boarded the HMS Cheshire at the Southampton docks. They crossed a rain-pelted English Channel to Ste. Mere Eglise, France, transferred to LCI’s and landed on the deserted Utah Beach, now littered with the battle wreckage left from the D-Day landing three months before. From here, the heavily laden soldiers marched to a bivouac area 10 miles inland to set up a tent camp in pasturelands and continue training. On Sept. 17, after marching to two other isolated bivouac areas, the 376th, along with the rest of the 94th, was ordered into its initial combat.

The division’s first assignment was to assist the French Army in containing more than 75,000 German troops and prevent them from leaving the areas around the submarine ports of St. Nazaire and Brest. Though no major assaults were ordered, individual fights often broke out along the miles bordering the German strongholds. Duty on the “forgotten front” (U.S. news sources alluded to it as such while the public concentrated more on the major battles further inland) consisted of the 94th carrying out numerous patrols into enemy territory to measure German strength and straighten out their own lines when Nazi forces attempted to break out. The enemy soldiers were strongly fortified, well fed and equipped. Many of them would hold out until the German surrender in May, 1945. Deadly and frequent skirmishes ensued along the 376th’s 22 assigned miles of fields and hedgerows with the desperate Germans determined to cut through the American and French lines and rejoin their comrades. On Jan. 1st, 1945, after 106 days, the 376th was relieved by the 66th infantry regiment, loaded onto “40 and 8” boxcars and sent to fill in the Allied line gaps during the last part of the Battle of the Bulge. Seven days later, Eisenmann and the 376th crossed into Germany, then joined the 10th U.S. Armored Division. In the ensuing battles, the tanks were to first thrust into the enemy forces and fortifications, while the infantry moved in behind to annihilate any of the remaining foes.

Beginning on Feb. 19, the 376th suffered in the unending ice and cold, sometimes sometimes without armored assistance against heavily defended positions with intense enemy artillery, machine gun fire and fierce counterattacks. While fighting with the 10th armored, the 376th forced a break in the Siegried Switch Line that allowed the tanks to slip through. On Feb. 22, they crossed the Saar River, joined by the 301st and 302nd infantries, and established the Ockfen bridgehead, allowing U.S. engineers to construct a heavy pontoon bridge at Saarburg. U.S. troops were then able to cross the river and take the ancient city of Trier.

On March 3, the 376th rejoined the 94th division, which had been assigned to head the Third and Seventh armies across the Rhine River. During the next 2 1/2 weeks, the 94th drove on over 100 miles through heavily defended enemy territory. Along the way they captured over 5,000 German prisoners and a vast quantity of supplies and equipment, much of which was crucial for the dwindling German armed defense. On March 22 and 23, after an intense barrage of German artillery (which killed many innocent German civilians), followed by deadly house-to-house fighting and sniper fire, they seized the city of Ludwigshaven on the banks of the Rhine. Because of their success in taking the city and surrounding area, the 94th had enabled the U.S. Third and Seventh armies to go on and destroy the German 7th Army, securing the battlefields west of the Rhine.

After 195 days of battle and over 17,000 prisoners taken, the 94th division was transferred to the 15th Army, where it assisted with the defeat of Germans in the Ruhr pocket. On April 22, the 94th division moved to Dusseldorf, while the 376th was split off to guard the town of Wuppertal and the surrounding areas of Remscheid, Luttringhausen and Lennep. Here they encountered 198 German work camps that housed more than 30,000 Russian, Polish, Italian, Yugoslavian, French, Czech, Belgian and Dutch displaced people who lived in deplorable conditions, and had served as slave laborers for the German war machine. Though not trained to take care of these people, members of the 376th did their best by supplying food, soap and other supplies, sparing what they could until organized relief could come later. This would be the final stage of operations for Eisenmann and his fellow warriors before the war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945. After V-E Day, the regiment left Wuppertal and traveled into Strakonice, Czechoslovakia to secure the treaty lines with the allied Russian forces.

Though the European war was then at an end, the battlefields in the Far East still raged on. The next assignment planned for the 376th involved fighting the Japanese in the Pacific Theatre, and taking part in the eventual invasion of the Japanese mainland. However, to the surprise and relief of many soldiers, this final conflict never occurred due to Japan’s total surrender on August 14, 1945.

With the war on both fronts was over, the men of the 376th spent their time going on short local leaves, or participating in the educational classes and sporting events provided by the Army, all killing time as they waited to return to the States. One of these sporting events featured PFC Howard Ladwig, a member of Eisenmann’s company who won honors against the 101st airborne track team when they competed in front of a cheering crowd at the Berchtesgaden stadium. Finally, the regiment’s turn to go home came, and PFC Eisenmann left Europe with his fellow soldiers on Dec. 20, 1945. Others in his outfit would follow until all of the 376th were back in the U.S. by January 1946. On Feb. 7, the regiment that had fought gallantly to help free Europe from Hitler’s armies was inactivated at Camp Kilmer, N.J.

During the war, more than 300 men of the 376th regiment were killed in action or later died of their wounds. Campaign streamers were awarded to the regiment for Northern France, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe. The 376th also received a Presidential unit citation along with individual awards of three Distinguished Service Crosses, 76 Silver Stars and 652 Bronze Stars.

Eisenmann was discharged in February 1946. He returned to Wisconsin and continued a very active, but much more peaceful life, finding careers in the construction and manufacturing industries. He married his wife, Mae, in 1948 and raised three children. In his spare time, he spent four decades as a volunteer Mishicot fireman along with enjoying years of hunting, fishing and gardening.

Eisenmann passed in 2000, one of the many “Greatest Generation” patriots who did their part to stop Adolf Hitler’s war machine from ravaging the people of Europe and the rest of the world.

(The author would like to thank Paul Eisenmann’s daughters, Carol Kunstmann and Jean Bateman, for sharing their father’s photos of his service in WWII.)

Looking for more stories about those who served? Here are a few more articles for your reading enjoyment.

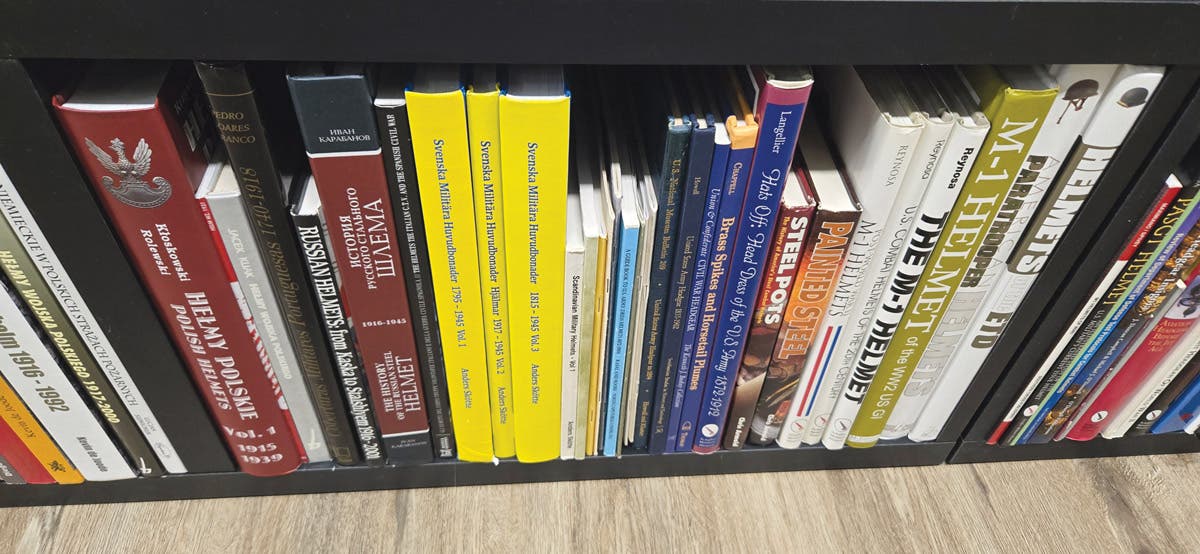

Chris William has been a long-time member of the collecting community, contributor to Military Trader, and author of the book, Third Reich Collectibles: Identification and Price Guide.

"I love to learn new facts about the world wars, and have had the good fortune to know many veterans and collectors over the years."

"Please keep their history alive to pass on to future generations".