Book Review: Insignia of the Death’s-Head Units 1933-1939, by Derek Chapman

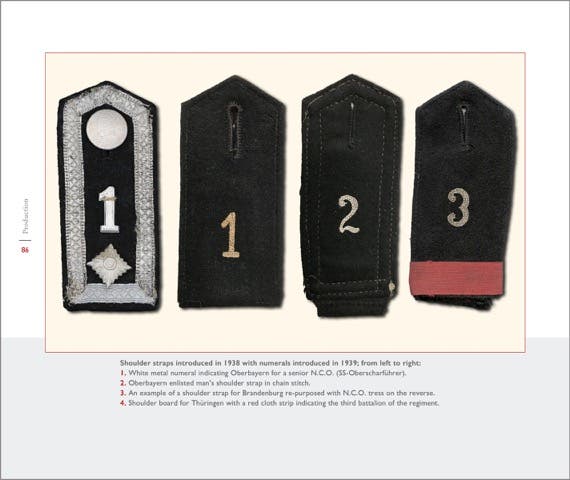

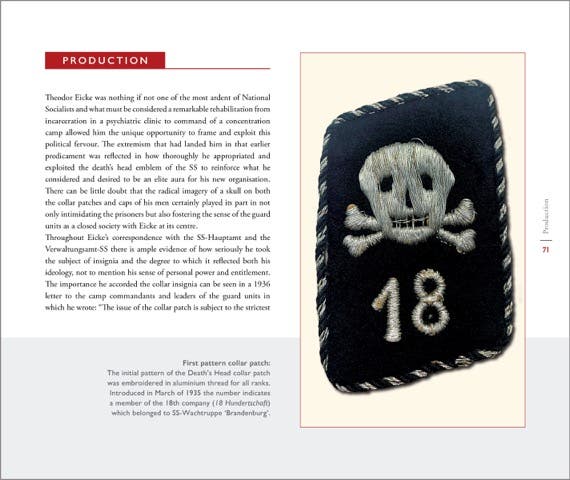

Chapters explore four SS-Totenkopfverbände insignia categories: collar tabs, shoulder straps and boards, cuff titles, and sleeve diamonds — and how they evolved before and during WWII.

Abzeichen der SS-Totenkopfverbände – Insignia of the Death’s-Head Units 1933-1939, by Derek Chapman, (no ISBN, publisher Blurb.com, 2021, self-designed, 98 pages, Hardcover, 8x10, numerous illustrations, $88.00)

Author/book designer Derek Chapman wondered whether a niche topic as such as concentration camp insignia would justify a book. Judging by responses in militaria and history forum threads, the answer is strongly affirmative.

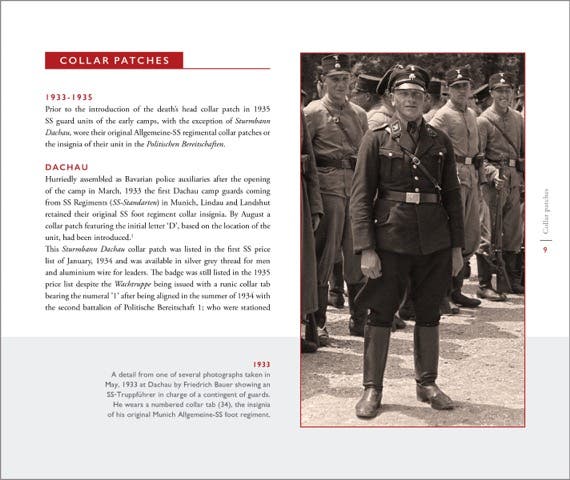

That’s because while all elements of the SS wore the Totenkopf (TK -"death's head") on peaked and side caps, in prewar years, the SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV) alone affixed the gruesome symbol to uniforms. (The exception being the dress tuxedo breast badge.)

Abzeichen contains chapters on each of the four SS-TV skull insignia categories: collar tabs, shoulder straps and boards, cuff titles and sleeve diamonds and how they evolved. For example, the straight-facing “pirate flag” design of the early 1930s became the subsequent “three-quarters looking right” variety. The latter would dominate in the prewar through 1945.

Chapman tackles all these things. The text is on-point, interesting without fillers or distractions.

The wartime images of insignia being worn and of surviving examples in private collections or museums range from pretty rare to surpassingly so. These include the special metal “TK” for shoulder strap, the short-lived Dachau “D” collar tab, skull-and-letter combination collar tabs, “mirror-image” skull tabs, official manufacturers’ template samples and on.

All specimens are well captured in high-resolution pictures. Most of the period shots are previously unpublished — both rare studio portraits and informal in-the-field ones of Totenkopfverbände members in various activities. These, alone, are valuable to uniform and insignia students trying to puzzle out interrelationships and evolution.

Also discussed and depicted are sword and bayonet knots, “old fighter,” and Reichswehr chevrons, sleeve eagles and the like. Another plus is related material of interest: TK enlisted and officer uniforms, earth-brown tunics, the “old type” crusher field cap with cloth visor, swords, daggers, equipment and more.

Rank charts are absent, but available elsewhere (for example, Andrew Mollo’s groundbreaking, six-volume series, Uniforms of the SS). Abzeichen pays homage to the Totenkopfverbände volume of Mollo’s 1970s study — the first serious attempt to unpack a challenging field. In fact, Mollo’s work remains impressive — especially given difficulties in sourcing data and imagery from East Germany before 1990.

Chapman told the MT, “Thanks to the internet [and to] specialist collectors … one of the key updates ... involved the opportunity to use a wealth of carefully researched period photographs to confirm and clarify the use of insignia.”

“This, Chapman, stressed, was “a luxury … unavailable to Mollo at the time of his publication. The book also documents several items of insignia specific to the unit that were not included in his earlier book.”

He concluded, “The digital ease with which one can now access period documents allowed me to introduce new information and internal correspondence regarding regulations, introductory dates and the exact unit distribution and allocation of badges; therefore … unraveling the confusion surrounding this abstruse system of regalia.” In addition to a strong bibliography, the author cites leading collectors and specialist authors as contributors.

Chapman usefully touches on administrative “turf wars” and not over just insignia. There were, he relates, intrigues aplenty among SS general Theodore Eicke, the commander and “Inspector” of concentration camps, and his boss, Heinrich Himmler, Oswald Pohl, and others.

Especially interesting are insights into the ambitious, micro-managing Eicke – who today would be dubbed a “control freak.” On Eicke’s goal of militarizing the TV, the author suggests Wehrmacht seniors would oppose the very idea of thuggish SS jailers forming military units, let alone accept fighting alongside them.

However, Chapman argues that Eicke (KIA Russia, 1943) plotted long to make this a reality.

In the event, while thwarted by Himmler in insignia matters (like adding the first initial of the all six SS-TV concentration camp names to respective units’ collar tabs), Eicke prevailed — Wehrmacht be damned.

Approval was granted to form the 3rd SS Panzer Division Totenkopf, with many of the original members drawn from concentration camp personnel. Eicke named himself commander.

Such notes and documentation go far in supplying behind-the-scenes context. Unsurprisingly, while military history records a good number of deeds of valor (several dozen 3rd SS men, Eicke included, won the Knights’ Cross) the division was responsible for a lot of war crimes, especially in Russia but also in France, i.e., the Le Paradis massacre of civilians.

Finally, this a high-quality book in all respects, well written, handsomely laid-out, thoroughly researched and systematically presented. It’s a great niche-filler. — David Walsh

You may also enjoy

*As an Amazon Associate, Military Trader / Military Vehicles earns from qualifying purchases.