Being There: The military life of WWII soldier Ted Weber part II

Part II of a fascinating trunk find of WWII memories from a man who was there.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: One of the articles from Ted Weber’s estate following his death was a large steel trunk containing a virtual time capsule from his 3 1/2 years in the U.S. Army Air Corps during WWII. Included in the cache were his uniforms, a few captured enemy souvenirs, over 600 personally taken photos, another 500 or so commercially sold pictures, and letters of correspondence with his friends and family. The crowning piece of the collection were his diaries: day-by-day descriptions in detail from his entry date of Jan. 7, 1942 (one month after U.S. forces were attacked, causing America’s entry into the war) through much of his time serving in the African and European theaters as a B-24 armorer. Weber’s diaries provide a historical “right there” perspective; describing his experiences of mundane training, constant relocations, tedious boredom and sporadic hardships intermixed with the sudden terror of enemy bombing and horrific air crashes during his time with the USAAF 345th squadron, 98th bomber group, serving in WWII.

Theodore Weber, a small-town Midwestern boy who had enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corp after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, was trained as an armorer and assigned to the 345th B-24 Liberator Squadron of the 98th Bomb Group. In the short time that followed, he had already experienced much of “army life” and now found himself in the frantic isolation of a busy Egyptian desert air base, doing his part to help defeat Hitler and the Axis powers.

Jan. 8, 1943, one year and one day after entering the army, Weber was promoted to sergeant. During his time in the Middle East, he had helped on a number of B-24s, keeping the guns, turrets and bomb racks operative in a harsh climate with its brutal sandstorms and extreme temperatures. He now worked on “Arkansas Traveler”, “Pluto”, “Floogie Boo” and other planes as each returned from their missions, had battle damage repaired and rearmed for their next sortie in the unending flights. The work was 24/7, rotating shifts readying for day and night missions, coupled with guarding and other duties. The end of January saw Weber and the squadron boarding another ancient African railroad train, steaming through the recent battle zone on the way to Libya. Blown-up trains, minefields, crashed planes and hastily dug German and British cemeteries littered the barren landscape as the train slowly plodded along towards Tobruk. They passed “Bambi”, a bomber that had been shot down during the battle, her wreckage strewn along the side of the tracks.

Thirty miles outside of Tobruk, the train stopped and the squadron disembarked at their new base. The large encampment was on a featureless flat desert plain, nothing but airplanes and tents stretching into the distance. Weber and several other soldiers put up their tent and settled in for their stay at this desolate post. Despite the daytime heat, the nights were bitterly cold. To combat this sudden dip in temperature, the tops of German and U.S. drums were cut off, stuffed with a mixture of sagebrush and gasoline, then burned to provide heat and light. The nights were extremely dark, as Weber found out on his way to guard “Gump the Sniffer”. He became disorientated in the pitch black and had to bribe a local passing Arab with a can of rations in order to get directions through the camp. The B-24s were now again busy with flights coming and going during both daylight and darkness, focusing on attacks in Sicily. The enemy retaliated by bombing the railroad line on the edge of the camp, sending Weber and the others into the slit trenches they had dug for their protection.

Soon, they were loaded into a convoy of trucks and on the move again, this time heading towards Tobruk. Weber noted the vast number of burned-out trucks, tanks and airplanes scattered all about the area. The harbor contained a number of sunken enemy ships intermingled with U.S. vessels unloading large shipments of supplies.

They passed Tobruk, drove through the port city of Derna, and then through the barren Libyan mountains. Along one treacherous mountain pass road were numerous buildings, their sides and fronts painted with the fascist colonists’ “El Duce” signs. The final destination on this trip was to the new base of operations in Benghazi, which Weber noted as a “total mess”. The fiercest battle damage could be seen starting five miles out of the city: mangled railroad cars and tracks, destroyed bridges, smashed planes, twisted and burned vehicles and an airport that had been totally wrecked. Signs were posted along the way, “Warning, Booby Traps”, to prevent souvenir hunters from being killed.

Outside of the city, the convoy stopped and the soldiers began setting up tents and lugging their equipment to their new “home”, the remains of Benina airport, but now a British and American shared installation. Weber and his comrades set up their shelter behind a B-24 named “Mongrel” and began digging a new slit trench in case the enemy bombers made another run at them. Weber foraged around, gathering scrap metal from a crashed JU88 to build a makeshift heat stove for the tent. He cursed Hitler for using so much “Ersatz” material in his planes when the newly installed stove pipe melted. Going back to the wreck, he cut a swastika out of the wrecked plane’s tail and packed it away for later. The 345th’s B-24s, having landed at the bases’ air strip, lost no time being reloaded. They quickly set off again to bomb targets in Naples. As part of cleanup effort of discarded enemy weapons, a stockpile of German bombs was hauled to the edge of the base, where ordinance men set them off, causing shrapnel to fly all over and damaging some Allied equipment.

On March 11, 1943, Weber was maintaining his newly assigned plane, “Snafu”, swabbing out the guns and loading ammo for the next run, when he was told a rumor that they were going home in 45 days. He tried not to get too excited, as he had come to know that rumors flew as often as the planes. He kept busy by working on “Cindy”, “Black Jack”, “Lucy’s Lucky 13” and his old plane, “Battleaxe”. Interesting, Weber fought a continuing problem of rust developing on machine guns — even in the dry desert climate. High-altitude flights at sub-zero temperatures and rapid firing caused a corrosion buildup that had to be cleaned on a regular basis.

More mishaps occurred. On landing, “Lil De-icer’s” front wheel locked up, causing the aircraft to nosedive into the runway. Later, when trying to salvage the plane, a member of the ground crew was crushed and killed when the fuselage tipped and pinned him underneath. Shortly afterwards, “Wimpy” crashed when returning from a night mission, lighting up the desert sky. “Lucy’s Lucky 13” undershot the runway and crashed, but all the crewmen escaped unharmed.

Weber noted that they were never alone at night since “sand fleas” kept them constant company. For daily functions, they improvised a latrine behind their tent using a 55-gallon drum, the top half cut off and contents regularly burned out with gasoline. The abundance of wrecked Axis planes came in handy since they used parts, such as those off an Italian bomber, to make tent “furniture”, a work bench and tent stakes.

Weber and a buddy were granted a rare leave, hopping a supply flight to Cairo, Egypt. They visited a few historic buildings, traveled to Giza to see the pyramids and managed to get acquainted with two British ATS girls. The foursome toured around Cairo for two days, but regrettably parted ways after spending a great evening at a Red Cross dance.

On April 7, “Snafu” was on a mission to Sicily when it came under heavy anti-aircraft, killing Lt. Marsh, the pilot, and causing heavy damage to the fuselage. As the B-24 came in for a landing, it crashed and caught fire. Escaping from the flaming wreckage, the crew was able to pull the dead captain’s body out with them. “War Cloud” was also badly shot up, but managed to land without incident. Later, a major general visited the Benghazi base and awarded Distinguished Flying Crosses and Silver Stars to some of the men who had flown in this, and other intense battles, over Sicily.

With “Snafu” gone, Weber was made crew chief on “Semper Felix”, a plane he stayed with for the longest period of his service, and a crew he came to know well and liked. “Semper Felix” started her missions by bombing Messina, Catania, Reggio and Augusta along the Sicilian coastline in rapid order. Weber and his crew were kept busy repairing and cleaning guns, turrets and bomb racks, shoveling out empty ammo casings and rearming the plane before each flight. During a brief break in the action, Weber and his fellow soldiers were very impressed when Captain Eddie Rickenbacker came to the field and gave a speech about his fighting in the Solomons. Weber wrote that Rickenbacker was an “all right guy, one who knew what he was talking about”.

“Semper Felix” continued to rack up missions by dropping frag cluster, 500 lb., 1,000 lb., 2,000 lb. and incendiary bombs on targets in SanGiovanni, Foggia and other Fascist cities. In between sorties, Weber would go up on test flights, joking with the crew and firing the guns to make sure all were in good order.

On June 13, Major Jones, the commanding officer of the squadron, was lost in a freak accident. “War Cloud” and “Cindy” collided while flying 2,000 feet over the Mediterranean Sea, resulting in the loss of both planes and all of their crew members. Major Jones had been piloting “Cindy”, while the squadron “hero”, Lt. K.K. Phillips was at “War Cloud’s” controls. “Semper Felix” and “Lil Joe” circled the area for three hours after seeing no one bail out, but found no survivors in the water. It was a very sad day for Weber and his comrades with the loss of two much-respected officers and their crews.

Italian paratroopers landed in the camp one night, killing several guards and blowing up two B-24s. In addition to single guards stationed by each of the planes, machine gun nests were set up around the field. Weber and another soldier sat in one of these for several nights, located next to “Snake Eyes”. This would have continued, but for Weber’s sudden malaria reoccurrence, sending him for a two-week stay at the field “hospital”(14 cots lined up in a long Army tent).

After Weber’s release, the B-24s of the 44th Bomb group landed at Benina to join on the bombing raids. “Semper Felix” took off on a mission to Messina, successfully bombing a railroad station, but returning riddled with ack-ack holes. Following a quick repair, she went on her 19th mission to Naples. On July 19, “Semper Felix” was joined by other B-24s, B-25s, B-17s and P38s to make a massive strike on Rome. Several days later, the squadron was entertained by a USO troop, but the show was suddenly cut short when a performing comic stormed off the stage due to a hail of rude wisecracks from the critical audience.

With all the death and destruction that Weber had seen, the worst was yet to come on August 1. Hitler’s “gas station” was located at Ploesti, Romania, and the 345th’s planes joined other groups in “Operation Tidal Wave”, a low altitude bombing mission to take out this valuable target. Of the 178 bombers that took part in the operation, 53 aircraft and 660 airmen were lost in this costly foray after being confronted by a massive force of anti-aircraft installations and intercepting fighters.

Anxious for his bomber to return after the horrific battle, Weber, waited until 1 o’clock in the morning, but “Semper Felix” never came back. The plane had been shot down, killing all the crew members on board. Ted listed those lost is his diary, noting; “Lt. Sulflow, Pilot, and Lt. Slinker, Co-Pilot could handle a B-24 with the best. Lt. Shay, the Bombardier was one swell little fellow. Friendly and pleasant, he seldom swore and never frowned or moaned or bragged. Lt. Millar the Navigator had really been around. Len Reger, Engineer, Treichler, Radioman, Meier, Top gunner, Patilla, Waste gunner, Sampson, Waist gunner and Sallus in “Little Ronnie”, his tail turret, were fellows I’ll long remember”. The crew had stood around joking with Ted before takeoff, making fun of the bombardier, “little” Lt. Shay. Lt. Sulflow commented “Yep, one horse. If anything goes wrong over there, you’re going to be the first human bomb to hit the target!” Recording that comment later, Ted felt sick, as when the good-natured jibe was made, the crew only had six more hours to live.

Casualties continued to mount. As “Kickapoo” from the 344th flew into Benina after the harrowing mission, all her engines suddenly quit, and she fell “like a rock”, exploding on impact. A slow procession of planes straggled in late, while others had to land in Sicily, Turkey or Ceylon. The bombing raid was so low that haystacks were knocked over, and “Daisy Mae” from the 415th came back with corn stalks stuck in her bomb bay. “Chug-a-lug” landed with Van Ess, the top gunner, badly wounded. The bombardier had taken over the damaged top turret, then given first aid to Van Ess, who later died. The plane also hit a barrage balloon cable, but luckily only dented a wing. “Chief” and “Black Jack” came in very late, both shot up badly with multiple flak holes.

The 345th sent out 12 planes on the mission, with seven not returning and six crews lost. “Snake Eyes” landed in Sicily, but was destroyed when it crashed into a stone wall; the crew able to get out unharmed. Another friend of Weber’s, Ray Gleason, had died on “Old Baldy” when it exploded in midair. Gleason had not been required to go on the mission, but did so anyway since he needed only 40 more hours of combat time before he would be sent back home to the States.

For gallantry in action, John R. (“Killer”) Kane, commander of the 98th bomber group, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Of the 345th’s planes that went on operation “Tidal Wave”, only three were left able to fly after minor repairs. These were quickly rearmed and sent on a mission to bomb Wiener Neustadt, Austria.

Weber, devastated by the loss of his friends, went back to work and waited for his next assignment.

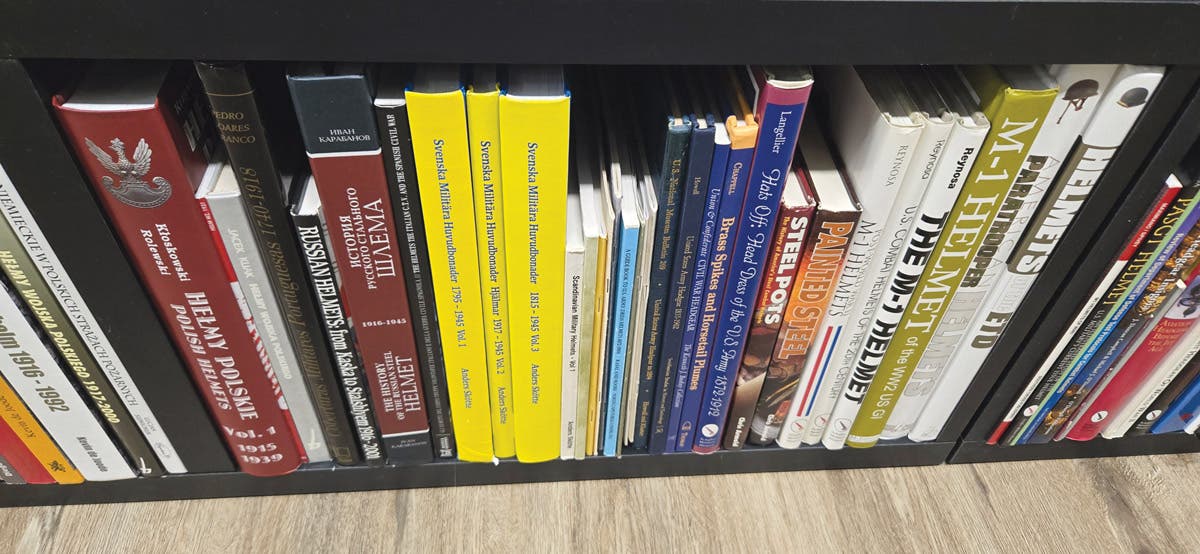

Chris William has been a long-time member of the collecting community, contributor to Military Trader, and author of the book, Third Reich Collectibles: Identification and Price Guide.

"I love to learn new facts about the world wars, and have had the good fortune to know many veterans and collectors over the years."

"Please keep their history alive to pass on to future generations".