The Original Monte Cassino Cross

During the battles for Monte Cassino, the Poles had almost 4,000 casualties, nearly half of the men involved.

When Poland was destroyed in 1939 with Hitler seizing the western half and his fellow mass-murderer, Stalin the eastern half, more than 1.7 million Polish men, women and children, disappeared into Soviet Siberia. 200,000 Polish soldiers and 14,000 Polish Army officers (few were ever heard from again) were captured. Almost 5,000 officers were discovered by Germans in April 1943, rotting in a mass grave in the Katyn forest, murdered by Stalin's secret police. Despite this genocide, the Polish Army was able to maintain its existence.

One surviving officer, Wladyslaw Anders, a commander of a Polish cavalry brigade, was captured and imprisoned in Moscow's infamous Lubianka Prison. In July 1941, following Hitler's invasion of Russia, Anders was freed and told that he was to form and lead a Polish army.

The Soviets allowed a Polish group of 40,000 sick and debilitated former prisoner/slaves to leave through Iran for Iraq (then under British occupation) in July 1942. They formed the two infantry divisions of the future Polish Second Corps.

In December 1943, the first reconstituted Polish division to fight, the 3rd "Carpathian" Division, entered into the lines in Italy, on the Adriatic Front as part of the British 8th Army.

General Anders was informed that his Polish 2nd Corps had been given the almost impossible task of capturing Monte Cassino and its destroyed abbey--the linchpin of German Field Marshall Kesselring's formidable "Gustav Line."

Built to keep the Allies from reaching Rome, the Gustav Line was the site of six months of brutal fighting during which the Allies incurred 350,000 casualties. Prior to the Poles arrival at Cassino, the U.S. Army's 168th Infantry Regiment of the 34th Infantry Division was ordered to attack Monte Cassino. Other regiments of the division were drawn into the battle but got nowhere. The under strength and badly mauled 34th Division had to be relieved by the 4th Indian Division, thus ending the first battle of Monte Cassino.

MONTE CASSINO

The ancient St. Benedictine Monastery, burial place of the founder of the Benedictine Order, Saint Benedict, stood top the Monte Cassino mastiff, 1,700 feet above the town of Cassino. It dominated the entire area for miles around.

Although the Allies always insisted that the Germans were using the abbey for an observation post, the Germans, commanded by Major General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin (coincidentally a Benedictine layman), remained true to their promise to the Vatican. They would not occupy the venerable building.

THE SECOND BATTLE

Despite having no concrete evidence that the Germans were using the building, the Allied Commanders decided to destroy the monastery. On Feb. 15, 142 B-17 "Flying Fortresses" dropped 253 tons of bombs on the huge building, followed by 87 low-level twin-engine bombers dropping another 100 tons. The monastery was turned into a jumble of ruins and more than 100 Italian refugees sheltering within it were killed. The destruction of such a venerated holy religious site became a propaganda bonanza for Josef Goebbles.

The Allies intended to mount an assault immediately after the cessation of the bombing before the stunned Germans could recover. The ruins had become an impregnable fortress, however. German paratroopers moved into the them almost as soon as the Allied bombing attack ended.

The 4th Indian Division was supposed to take the ruins but was not even informed of the intended bombing. When they mounted them after midnight on Aug. 17, they managed to only get within 800 yards of the monastery before being repelled by the well-entrenched German paratroopers. The two Gurkha battalions of the 4th Division suffered 249 men killed, wounded or captured and nearly all of their officers. This ended the second battle of Monte Cassino--another futile effort.

THE THIRD AND FOURTH BATTLES

The third battle for Monte Cassino began on March 14. Again, the 4th Indian Division led the assault. The battle ended 12 days later on March 26, leaving the division shattered. The British 78th Division moved up to take its place. The 4th Indian Division was moved to the Adriatic Front to be rested and rebuilt.

The 78th Division held the line until mid-April when the Polish 2nd Corps (consisting of the 3rd "Carpathian" infantry Division, the 5th "Kresowa" Infantry Division and the 2nd Polish Armored Brigade) took over the position. On May 12, the Poles charged the monastery's ruins. During reckless and ferocious hand-to-hand combat with the paratroopers, the Poles incurred such grievous losses they had to withdraw.

They attacked again on the evening of May 16, and again, fought man-to-man. The Polish soldiers captured, lost and recaptured strong points again until they began running out of supplies and ammunition. The Poles eventually had to resort to throwing stones at the Germans.

Because the losses were so high, the Poles had to comb the rear areas for clerks, cooks and drivers who they armed and sent up the mountain. It was all in vain. The Germans still held the monastery at the end of May 17.

The following day, as the Poles prepared for another assault, a white flag appeared above the ruins. The paratroopers had taken serious irreplaceable losses in the Polish attacks. After the surrender, Lt. Kazimierz Gurbiel of the 1st Squadron, 12th Podolski Lancers led a 12-man patrol up into the ruins. He was to raise the Polish flag above the rubble, but no Polish flag could be found, so the pennant of the Podolski Lancers was the first flag to be raised in victory.

A day later, General Anders climbed the mountain and had the Polish troops hoist a British flag above the monastery ruins. Anders recalled corpses of Poles and Germans entwined in a deadly embrace as they died together in vicious combat.

During the battles for Monte Cassino, the Poles had almost 4,000 casualties, nearly half of the men involved. Atop Mount Calvary (Hill 593), the last German position to fall, a monument dedicated to the memory of the 1,100 Polish soldiers lying in the Polish cemetery reads,

We polish soldiers

For our freedom and yours

Have given our souls to God

Our bodies to the soil of Italy

And our hearts to Poland

THE MONTE CASSINO CROSS

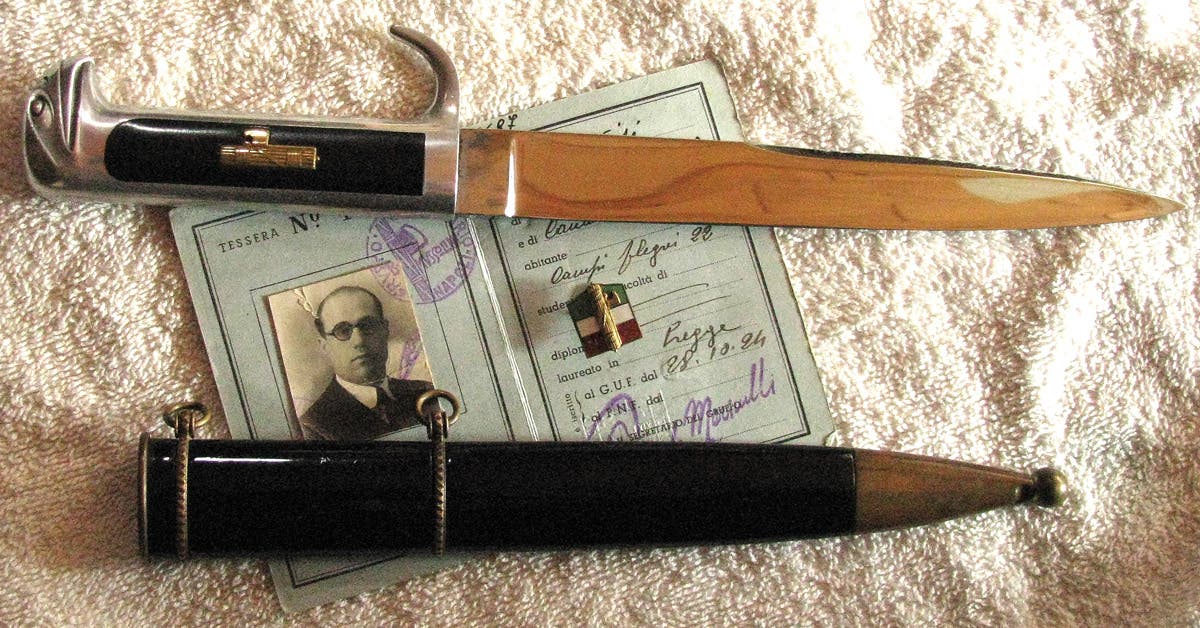

In 1951, the author bought a Monte Cassino Cross from "Esperia" in Piazzetta San Marco in Venice, a shop selling medals, insignia and souvenirs of Venice such as postcards and guide books. The owner had been an old "Blackshirt" and had fought in Ethiopia and Spain. He explained that this Cross had been made in Italy on order of the Poles, in 1944, but couldn't remember the name of the manufacturer.

Obverse and reverse of the Monte Cassino Cross, first issue. The wartime-produced version measures 38mm across. Postwar examples are 40mm across. Photo by Ron Leverenz, Doughboy Military Springfield, MO

In his book, Polish Orders, Medals, Badges and Insignia, Military and Civilian Decorations, 1705-1986, Dr. Zdzislaw P. Weslowski states that the Cross was established in May 1944 and was awarded in the field (during and after the battle) to all Polish troops participating in combat at or near Cassino. He stated that the Polish Government in exile in London authorized the medal and awarded 49,895 examples.

The Italian-made cross is a black cross fleury, the four arms measuring 14mm wide emanating from a square center with 10mm sides (overall, the Cross' width is 38mm). The obverse square is incised "MONTE/CASSINO/MAI/1944" in four lines. The revers e square is blank.

The Monte Cassino Cross is made of an inferior wartime metal, probably zama, a compound of zinc, aluminum and magnesium. Spots of oxidation appear on the reverse square (one of the faults of the "ersatz" metal). The cross is suspended from a 33mm wide ribbon with 11 equal stripes--6 blue and 5 red. Needless to say, these original wartime-made crosses are quite rare and seldom found.

The cross is suspended from a 33mm wide ribbon with 11 equal stripes--6 blue and 5 red. Wartime crosses have a blank square on the back. Later crosses have a serial number stamped into the reverse square center. Photo by Ron Leverenz, Doughboy Military Springfield, MO

The second type (postwar) Monte Cassino Crosses are made of dark bronze and are 40mm wide, versus 38mm of the original. The later Crosses have a serial number stamped into the reverse square center.

Whether a wartime or postwar piece, a Monte Cassino Cross is highly prized by any Polish veteran. To such soldiers, it represents a battle that many call "the hardest fought battle of World War II."

Clem graduated from Jesuit Catholic Preparatory School in New Orleans in 1948, joined the US Navy Reserves, served in the US Army Signal Corps during the Korean War and attended the US Merchant Marine Academy.

He served 30 years aboard numerous merchant ships which allowed him to pursue his childhood passion of collecting military insignia. During his seven years of sailing in and out of Vietnam, Clem acquired an unimaginable collection of Vietnam War insignia. Every country’s port was a gold mine of tailor shops and junk stores.

In 1989, Clem took over the Vietnam Insignia Collectors Newsletter from Cecil Smyth. He quickly became the de facto overseer of the hobby.

Clem contributed numerous articles on various military insignia to Military Trader and Military Advisor. Clem died at the age of 87 on 3 February 2018. His knowledge and expertise will be missed. He will long be remembered. — Bill Brooks