Empire Protector: The Martini-Henry Rifle

Many shots have been heard around the world. And each time it was fired from a different rifle. During the Victorian era, that rifle was the Martini-Henry. This brief history and collecting tips will provide you with what you need to know before you buy.

Many shots have been heard around the world. And each time it was fired from a different rifle. During the Victorian era, that rifle was the Martini-Henry.

At the end of the 1964 film Zulu, which chronicled the events of the almost infamous frontier outpost of Rorke's Drift along Zululand where approximately 100 British soldiers fended off an attack by some 4,000 Zulu warriors, Stanley Baker replies that the victory wasn't merely a miracle, but rather, "a short chamber Boxer Henry .45-caliber miracle." Whether the real Lieutenant John Chard ever said such a statement is certainly lost to history, but the fact remains that the cartridge and the weapon that fired those bullets played a very decisive role in determining the outcome.

In many ways, the British conflict with the Zulu has become symbolized by the rifle of the day, as much as the red jackets and tropical sun helmets worn by the European combatants. This rifle is the Martini-Henry, and today it has become a favorite among collectors.

"As for the Martini-Henry, there seems to be a serious brand of collector, to whom 'black powder' weapons and early contained cartridge weapons are seen as the 'purest form,'" says Gary Jucha, an advanced collector of English militaria. "Since the 'classical' English defense of Rorke's Drift, the Martini-Henry has been the embodiment of the classic Victorian 'last of the line — English through and through' persona."

If one considers it fair to say that the Colt Peacemaker tamed the American West, then it should be equally accurate to say that the Martini-Henry was the weapon that maintained order around the globe. From the dark continent of Africa to the jewel of India to the Far East, the sun never set upon the British Empire or its warriors wielding the Martini-Henry during the second half of the 19th Century.

Age of Rifles

Following the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, the age of the smoothbore musket was coming to an end, and over the course of the next 50 years, firearms with rifled barrels and breech-loading operation would transform modern warfare. Likewise, this was a time of great expansion by the European powers, and none so great as the mighty British Empire. Although advanced Martini-Henry collector Jason Atkin, whose personal collection includes more than 20 of the classic rifles, sees the weapon as more of "guardian" of the existing empire, he admits that its place in history is certain.

"I personally feel that such a moniker as 'empire builder' would be more aptly applied to the Brown Bess Musket, or the P53 Enfield Rifle," Atkin emphasizes, adding "Tremendous amounts of expansion occurred during the tenure of those weapons. This isn't to say that the British Empire didn't expand during the time of the Martini-Henry."

Introduced in 1853, the Enfield Rifle was a muzzle-loading, rifled musket that had a range of about 1,000 yards. Updated in 1867 as the Snider-Enfield Rifle, it incorporated a breech system that was invented by Jacob Snider of New York. This involved the removal of two-inches of the butt end for a breech loading system using the new brass cartridge ammunition. The space behind the cartridge was closed with an iron breechblock, hinged to the right side of the barrel.

The 1860s and early 1870s were a time of great conflict, and the British closely observed the wars around the world, including the American Civil War (1861-1865), the Danish-Prussian War (1864), the Austro-Prussian War (1866) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). The adoptions of the Prussian needle-gun and the French Cassepot Rifle were indicators that Great Britain needed to update the aging Enfield Rifle. The result was the stopgap Snider-Enfield as an interim measure, and made good use of the huge stockpiles of P53s that the British possessed. While these weapons are considered classics to gun collectors today, it was clear to military planners of the day that a suitable replacement was needed.

That replacement would be the Martini-Henry, a rifle that some argue should be properly designated the "Peabody-Martini-Henry." It is actually a Peabody pattern that was further modified to a self-cocking hammerless design of Friederich von Martini of Frauenfeld, Switzerland, along with the rifling design of Edinburgh gunsmith Alexander Henry. The Peabody was an American designed rifle which was first patented in 1862, but was fully developed too late to have an impact in the American Civil War.

The firearm is a breechloading central-fire weapon, meaning that the cartridge is loaded into a chamber at the rear of the rifle. This enables the soldier to reload quickly and fire more rounds than the previous muzzle loading methods that required that the projectile be loaded down the barrel. A small lever operated and lowered the breechblock, and allowed a cartridge to be inserted into the chamber, which returned the lever to the former position and closed the breech. The breech is centrally pierced to accommodate the firing pin, which was driven forward by pulling the trigger. Lowering the lever ejected the fired cartridge and a new one could be placed. Thus, several more rounds a minute could be fired, and a soldier could remain in the crouched or prone position--clearly a benefit over the traditional muzzle-loading firearm!

The Martini-Henry weighs about nine pounds and is just over four feet in length. It fires a hardened lead bullet with a muzzle velocity of 1,350 feet per second, and the weapon is sighted for up to 1,000 yards. It was also the first English service rifle designed as a breechloading rifle. Later versions of the Martini-Henry improved upon the design by incorporating other rifling patterns, including the Metford System and even a system designed by Enfield. These later versions are often referred to as "Martini-Enfields" and "Martini-Metfords."

The first true Martini-Henry adopted for service in the British Army was designated the Mark I and entered into service in June 1871. Additional rifle variations followed and include the Mark II, Mark III and Mark IV, as well as an 1877 Carbine version. Variations of these later weapons included a Garrison Artillery Carbine, as well as Artillery Carbine Mark I, Mark II and Mark III. There were even versions smaller in size designed as training rifles for military cadets.

Originally, the British adopted the Short Chamber Boxer-Henry .45-caliber black powder cartridge--the one that Stanley Baker's Lt. Chard seems to h ave had so much faith in. Later, this was replaced by .402-caliber ammunition, and even the later .303-caliber. Because of upgrades of existing stockpiles of rifles and conversions, these weapons are found today in a variety of calibers. As these rifles tend to be well over 100-years old, firing them today should be done with extreme caution. As with any antique rifle, a competent gunsmith should inspect the weapon to certify that it is safe to shoot.

Defending the Empire

What has made the Martini-Henry such a durable, and collectible, piece is the fact that it was an extremely well designed firearm for its day. It was not revolutionary, but firearms don't have to be revolutionary to be successful. "It pains me to say this, but the Martini-Henry did not really usher in any major technological strides in terms of firearm design," emphasizes Atkin, who suggests that the weapon was rather Milquetoast. "The biggest headline about the Martini-Henry is that it was the British Army's first true breechloading cartridge rifle."

Atkin further stresses that the ease of manufacture, which the British were sticklers for, resulted from a rifle design that used the least amount of moving parts possible. The simplistic design made these rifles cheaper and easier to build and, more importantly, offered improved rate of fire and superior accuracy. "Remember, by the time of the Martini's introduction into service, repeating rifles such as the Winchester were widely available," explains Atkin, who adds that the British found the popular American rifle too complex and unreliable to consider for widespread military issuance. "They also did not care for the puny ballistic characteristics of these repeaters."

For Queen Victoria's little wars around the globe, the rifles, single shot as these were, would be suitable against the various forces that the British Army faced in the field. "It was more or less the last of the line of semi-craftsman's rifles that had a big bore and a 'big bite,'" suggests Gary Jucha. After the Martini-Henry, the nations of Europe turned to smaller caliber mass-produced weapons that could fire at a faster rate but lacked the big, heavy rounds. "It was the end of the era."

The Martini-Henry saw service around the world, but mostly under the Union Jack, as the rifle was exclusively in the service of Great Britain. "However, Martini variants were used by a plethora of countries," adds Atkin. The short list includes Afghanistan, Austria, Belgium, Turkey, Japan, Romania, Nepal, Egypt and the Sudan.

As touched upon, the Martini-Henry underwent several caliber adjustments during its service in the Queen's army, and the final change came about when the Martini was converted to the smaller .402-caliber ammunition. In fact, the final version, the Martini-Henry Mark IV actually started out as Enfield-Martini .402-caliber rifles, when the British saw the benefits of the higher velocity, smaller caliber rounds over the massive but slow moving .450 bullets. As a result, the British were faced with having to worry about supply for .303, .402 and .450.

The decision was made to convert the Enfield-Martinis back to the .450-caliber and supply these Martini-Henry Mark IV's to non-frontline troops in the far-flung colonies. Atkin stresses on his Web site (www.martinihenry.com) that this is the reason today why so many Mark IV's come from India, Nepal and Pakistan.

Following the first Sudan War, the decision was made to provide a smaller caliber, but higher velocity rifle to the troops. In 1887, the Lee-Metford Rifle was adopted. It featured a magazine that held eight rounds, while the Mark II version would increase the magazine capacity to 10 rounds. The Lee-Metford would be replaced in 1895 by the Lee-Enfield, the Metford system being the final British rifle to use a black powder propellant.

However, with the introduction of the Martini-Henry Mark IV, which remained in production until 1889, the rifle remained in service throughout the British Empire through the First World War. In fact, many native volunteers in British East Africa engaged the Germans through four years of war with the same rifle that served the British frontline forces for more than 30 years.

Collecting the Martini-Henry

Antique firearms from the 19th century are a very specialized area, and one that was typically overlooked by collectors. Prices for vintage World War I and World War II rifles have typically tended to be higher than those from the Victorian Era--however American Civil War firearms have always been in high demand. It should be noted that firearms manufactured prior to 1898 do not require any form of Federal Firearms License, but you should check with local and state laws prior to purchasing any firearm.

Until the film Zulu came out, many gun collectors may have never even heard of the Martini-Henry, and Atkin stresses that it was very much that film that sparked his interest. "These rifles were a dime-a-dozen and were sold off as surplus chump-change until the 1964 release of "Zulu." The film popularized the Martini, and thus collectors snapped them up left and right."

In the past decade, probably due to more collectors having access to one another thanks to the Internet, the rifles, as well as the P53 Enfield Rifle and Snider-Enfields, have become extremely sought after. Says Atkin, "Collectors snapped them up left and right, with Australia and New Zealand being excellent sources up until about five years ago."

Recent caches found in Nepal have softened the market and slowed the skyrocketing values of these weapons, which currently go for about $600 to $700 for a 1880s-dated weapon in good to very good condition, and $750 to $900 for an 1870s dated weapon in similar condition. No doubt collectors are willing to pay a bit more for the early dates, as it evokes the 1879 Zulu War. And it is worth pointing out that a rifle with an 1870s date doesn't mean it was anywhere near South Africa.

Most collectors, including Atkin, agree that once the existing caches are sold off the values will probably start marching upwards again. So if you've ever wanted to own a piece of history, this might be the time to buy.

There are some words of caution. Again, the rifles are typically sold online, as being "1870 Pattern" or "1880 Pattern" and this is important, as it is just a marketing term. "The British never used the 'Pattern 1880' designation for the weapons," explains Atkin. "Rather, the rifles were referred to by the mark of the arm: Mark I, Mark II, Mark III, or Mark IV."

A so-called "Pattern 1880s Short Lever" could be a Mark II or a Mark III, as the short lever was present with Mark I, II and III versions but only the II and III were manufactured in the 1880s. Likewise, the "Long Lever" moniker, according to Atkin, should only be applied to Mark IV rifles. And while these will always be 1880s, they might be the ones found in best condition. "These have been the true gems of the collection. They're the newest rifles and therefore, are in the best condition of the lot."

Collectors also agree that the original Mark I is the most sought after, in part because many were in fact upgraded to the Mark II pattern. Thus, original Mark I Martini-Henrys have become the "Holy Grail" for advanced collectors. Don't expect to find one simply by ordering one online; while you might get extremely lucky, most of the 1870s rifles are Mark IIs and even Mark IIIs.

The other thing that collectors must be cautious of is non-military Martini-Henrys. These were made in Birmingham for civilian use and are not considered a military collectible. They are not as common as the military variety however, and most Martini-Henrys are in fact the military version.

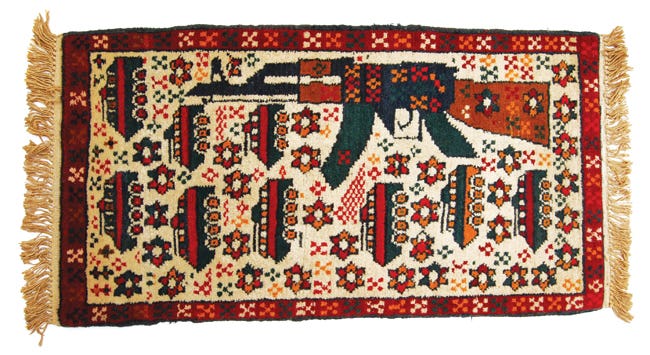

Likewise, another type of Martini-Henry is encountered more frequently: the so-called knock-off from the Khyber Pass region of Afghanistan. Atkin tells that these are easy to spot, as the "N" in "Enfield" on the side of the gun is backwards. These rifles were reproduced in the same region where the British mounted several invasions into Afghanistan.

The region is also known as a hotbed of gunsmiths, who have been copying dozens of other guns for more than 100 years. Atkin has suggested that stories abound that today the same skills are applied towards making unauthorized copies of the AK-47 assault rifle! While these rifles have circulated around the region for years, these weapons are only now beginning to reach international markets. With the advent of the Internet, this will likely rise, but the number of fakes is actually small compared to genuine Martini-Henrys.

"There are not enough minor details that add high values, unlike Colts and Winchesters," adds Keith Doyon, a long-time collector of Martini-Henrys and variants. He says that at the current time, it is too expensive to produce quality copies of these rifles, but adds that, "Copies will start to be made in the next five to 10 years as prices for originals go up."

Today, enough legitimate Martini-Henrys abound that collectors can easily track down a good one without fear. But, as with all collectibles, it is advisable to buy from a reputable dealer and be sure to ask about refunds if you are buying from a catalog and can't see the exact weapon prior to purchase.

Once in the collection, these weapons should not be restored, unless by a professional gunsmith or someone experienced with restoring antique firearms. There are also differing opinions on the cleaning methods used on historical militaria. Some would argue never to over clean the wood or metal hardware of an antique weapon, especially if it is not intended to be fired. Others would say that as with any gun these can, and should be cleaned, as it was part of the regular process. Field stripping such an old weapon should be done with care, if at all.

"Clean, (to remove) dirt and crud, but no more," says Doyon. "Its patina is part of its heritage. European collectors (often) apply different standards, they like shiny bright. Not so with U.S. collectors. Besides, they are rarely ever safe to shoot with original loadings so some day someone may want to truly restore it to shooting condition, and you don't want to have stripped off its collectible value."

Protecting an antique firearm can be done without completely cleaning away the history. Jason Atkin, who admits that he overdid it with his first Martini-Henry, suggests that collectors can attempt to clean up and remove surface rust with a bit of 0000 steel wool and some light oil. Whether the preference is for a nice patina or a shiny look, of course will be left up to the individual. But as mentioned, do not attempt to fire any antique rifle unless it is inspected and deemed safe to do so.

As a classic piece of British military history the Martini-Henry more than proved its worth. While it never was a frontline weapon against another European army, it will likely be remembered as one of the most important tools that held the Empire together and served the Soldiers of the Queen.

"It served from England to Africa to India and Nepal, to Australia-New Zealand from the early 1870s to damned near the end of the century," says Keith Doyon, emphasizing that was during a time of incredible technological evolution. "Collect one of these and you too can battle overwhelming odds against the Zulu and participate in the pageantry that was colonial 'Innjah!'"

You may also enjoy

*As an Amazon Associate, Military Trader / Military Vehicles earns from qualifying purchases.

Peter Suciu is a freelance journalist and when he isn't writing about militaria you can find him covering topics such as cybersecurity, social media and streaming TV services for Forbes, TechNewsWorld and ClearanceJobs. He is the author of several books on military hats and helmets including the 2019 title, A Gallery of Military Headdress. Email him and he'd happily sell you a copy!