Italian Medal for World War I

In extraordinarily difficult fighting in the most inhospitable area in Europe—the Alps—Italian troops persevered. A Royal Decree created a ribbon for service in this war.

By Clement V. Kelly

After some hesitation, Italy decided to enter the “Great War” by declaring war on her former ally, Austro- Hungary, on May 23, 1915. Italy initiated hostilities when she sent into the Trentino. It would be 14 months before she declared war on Germany, despite German troops joining the Austrian forces in fighting Italy, and German submarines sinking Italian merchant vessels.

Italy mobilized 5,500,000 men during the war. By the end of the conflict, 2,200,000 had become casualties—665,000 of whom were killed. In extraordinarily difficult fighting in the most inhospitable area in Europe—the Alps—a battlefield where peaks rose to over 13,000 feet and glaciers were hundreds of feet thick, the Italian troops persevered.

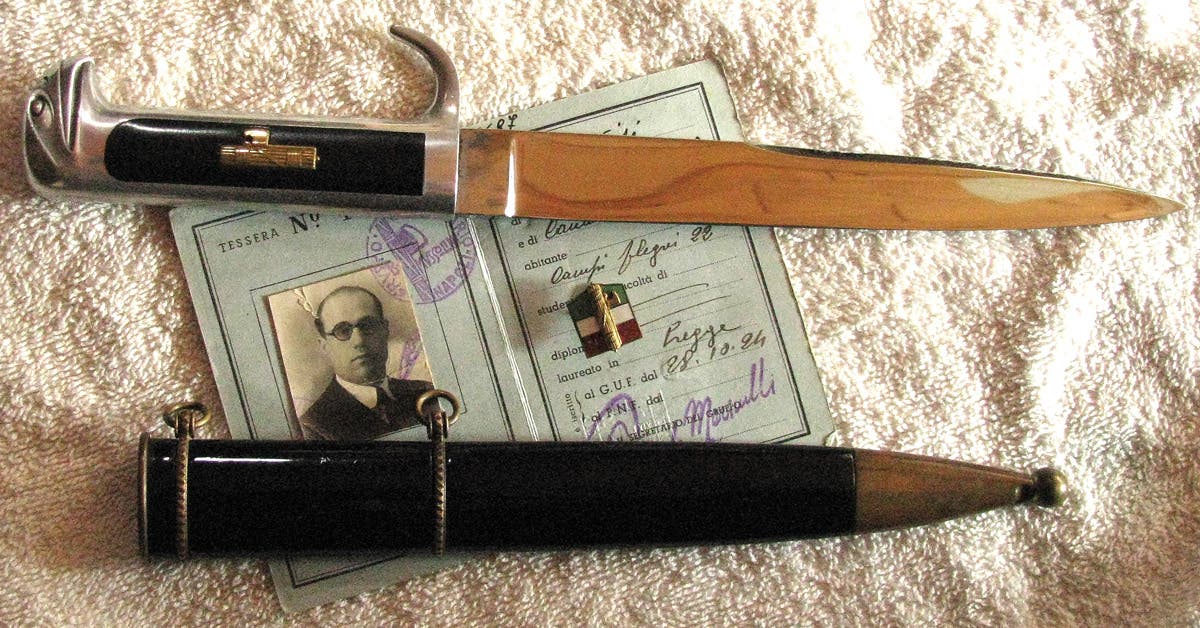

ITALIAN MEDAL

The Italians considered this war to be a continuation of their endeavor to unite all areas of Italy into one nation (a struggle begun in 1848) by acquiring the “unredeemed territories”—the parts of Italy still held by Austria. A Royal Decree, number 641, of May 24, 1916, created a ribbon for service in the war. This was followed by another decree, number 241, of July 29, 1920, that instituted a medal to be suspended by this ribbon, named the Medaglia commemorativa delIa guerra 1915-1918 per il compimento dell’Unita d’Italia (Commemorative Medal for the War 1915-1918 for the Completing of the Union of Italy.)

The bronze, 32mm-diameter medal (one variant is 42mm) bears the effigy of King Victor Emmanuel III in military uniform, wearing an Adrian-style helmet. Around the edge it reads, “GUERRA PER L’UNITA D’ITALIA 1915-1918” (War for the Unity of Italy 1915-1918). The reverse has a figure of “Winged Victory” standing on shields held aloft by two helmeted soldiers and around the edge it reads, “COINATA N.EL BRONZO NEIVIICO” (Coined from enemy bronze).

Theoretically, these medals were made from captured Austrian bronze cannon, however with a multitude of firms in Italy producing these medals by the millions, it is unlikely.

The medal was designed by the sculptor S. Canevari and his name is behind the neck of the king on most strikings. The suspension ribbon is the same as the ribbon used for the first (1865) Medal for the Independence and Unity of Italy, in the colors of the Italian flag: green, white and red stripes repeated six times. Again, this was an indication that this war was a continuation of the process of unification.

Medal bars for Albania 1918 and Albania 1920.

AWARD OF THE MEDAL

The medal was awarded to all armed forces personnel with a minimum of four months service within the area of military or naval operations. It was also given to civillians who assisted the armed forces, Red Cross workers, Sovereign Military Order of Malta members, volunteer American ambulance drivers (one was Ernest Hemingway who was also awarded the Silver Medal for Military Valor and four War Merit Crosses).

It was also given to the British, French and American soldiers and aviators who came to Italy to augment the Italian Army after the disaster at Caporetto. Other lesser knowm Italian groups qualifying for the medal included members of the Distaccamento Garibaldi (Detachment Garibaldi) raised by Garibaldi’s grandsons and consisted of more than 2,000 Italians volunteers to the French army to fight the Germans before Italy entered the war.

The men of the Italian Expeditionary Corps in Syria and Palestine who served with the British fighting the Turks for 24 months (1917-1919) and participated in the occupation of Gaza and Jerusalem, also received the medal. The post-WWI Italian detachments that were part of the Allied Expeditionary Corps sent to Russia—the Distaccamento Iridenti (more than 3,000)—and the Distaccamento Savoia at Murmansk (1918-1919) were also given the medal.

MERCHANT MARINE MEDAL

A July 15, 1923 decree (number 1786) established a medal for merchant marine personnel who had participated in the war. This was actually the same medal but with a different ribbon consisting of 11 alternating stripes of blue and white. This ribbon had been first used on the Cross for War Merit, but only briefly.

The merchant mariners were not enthusiastic about the blue and white ribbon. They preferred to wear their medal suspended from the green, white and red ribbon as used by other veterans.

MEDAL BARS

Bronze bars or clasps that slipped over the ribbon were authorized for wear on the suspension ribbon of both medals (armed forces and merchant marine). These copied the bars found on the aforementioned independence medal of 1848-l870, once again alluding to the premise that the war was a continuation of the struggle to unite Italy.

The bars are approximately 38mm wide and 6mm high, with some slight variations noted due to the great number of manufacturers. They are in the shape of laurel leaves with a ribbon in the center at an angle, bearing the single year numerals 1915, 1916, 1917 or 1918.

Because of unrest in Albania—supposedly incited by Austria and causing the abdication of the throne by William, Prince of Wied—Italy found it necessary to frequently intervene in that country to preserve order, beginning with the occupation of Valona in 19l4. Therefore, a bars was authorized reading “ALBANIA” above the single year numerals 1916, 1917, 1918, 1919 or 1920.

When the ribbon bar was worn alone, possession of a clasp was denoted by a five-pointed star either in silver metal or silver wire embroidery, to a maximum of 4 stars per ribbon. If more clasps were awarded (such as for a man who had served for years in WWI and again in Albania), an additional ribbon bar was allowed to be worn. Often, men who had served in Russia in 1919 and 1920 would add these bars to their medals, but this was unofficial and not sanctioned by any of the statutes.

DISTRIBUTION AND AVAILABILITY

By royal decree, the medals were to be provided by the government at no cost to the recipients, something seldom done in Italy. Usually, recipients were required to purchase their own medals. As a result, it is common today to find the medal—whether due to carelessness, ignorance or just plain indifference—suspended from a ribbon which is reversed, with the red stripe beginning the series at the wearer’s right, instead of the green stripe as prescribed in the statutes.

These are well designed, attractive medals which are available to collectors at reasonable prices. Of course, those with bars are priced a bit higher. Those with the scarcer Albania bars, higher still. These medals would certainly enhance any collection of medals from the “Great War”.

CLICK HERE to share your opinion or knowledge in the Militaria Message Board

Clem graduated from Jesuit Catholic Preparatory School in New Orleans in 1948, joined the US Navy Reserves, served in the US Army Signal Corps during the Korean War and attended the US Merchant Marine Academy.

He served 30 years aboard numerous merchant ships which allowed him to pursue his childhood passion of collecting military insignia. During his seven years of sailing in and out of Vietnam, Clem acquired an unimaginable collection of Vietnam War insignia. Every country’s port was a gold mine of tailor shops and junk stores.

In 1989, Clem took over the Vietnam Insignia Collectors Newsletter from Cecil Smyth. He quickly became the de facto overseer of the hobby.

Clem contributed numerous articles on various military insignia to Military Trader and Military Advisor. Clem died at the age of 87 on 3 February 2018. His knowledge and expertise will be missed. He will long be remembered. — Bill Brooks