When it comes to historic relics, avoid “gilding the lily”

Avoid these three methods of establishing backward provenance of historic artifacts

Whether a helmet, bayonet, uniform, or Jeep, one of the most tired expressions in our hobby begins with, “If only this X could talk…” A pointless statement, because we all accept that inanimate objects can’t speak. Often, when I hear someone say that, what I really hear is, “I haven’t done any research, nor do I plan to…”

Researching the history behind the relics or vehicles we love can sometimes be hard — even impossible. Regardless, most serious students of history understand that the relics we collect are the direct conduits to the stories of soldiers who served and sacrificed. This drives us to uncover whatever tidbits of history we can find to associate that rifle, medal, or weapons carrier with a particular time and place.

Gilding the Lily

Whereas most of us are familiar with the expression, “gilding the lily,” it is actually a twist of a phase William Shakespeare wrote in his play, “King John.” Shakespeare’s actual phrase was “to paint the lily” and comes from Scene II when Salisbury says to King John (and Pembroke):

“Therefore, to be possess'd with double pomp,

To guard a title that was rich before,

To gild refined gold, to paint the lily,

To throw a perfume on the violet,

To smooth the ice, or add another hue

Unto the rainbow, or with taper-light

To seek the beauteous eye of heaven to garnish,

Is wasteful and ridiculous excess.”

So who among us are guilty of this when talking about items in our collection?

I am. And so are many others.

In the Fifth Grade, I "gilded the lily"

It is understandable, when explaining the history of an object we sought out, purchased, preserved, or even restored, to try to emphasize to others what we believe to be its significance. However, it is too easy to convince ourselves of a history we want to believe.

In fifth grade, my history teacher tasked us with compiling our family genealogy. Not satisfied with the historical record I could find in family bibles, the county courthouse, or the published histories that all showed that my Germanic families arrived in the United States between 1848 and 1856, I was determined to find evidence of my Graf or Hoffmann families having served in the American Revolution, some 70 years earlier than their documented arrival in North America.

Doing the math, I concluded that I needed to link at least two generations to get back to Continental soldiers who had the surname found in my ancestry: Graf or Hoffmann. Back in those days, we relied on the magazine Genealogical Helper to link to other researchers with similar pedigrees. Looking through the index, I found an entry for “Hoffmann.” Flipping to the query, I discovered someone looking for “Nicholas Hoffmann” who served in the Pennsylvania militia during the Revolution. I had my man! After all, my great grandfather was named “Nicholas Hoffmann.” The problem was, I knew my great grandpa didn't arrive in the United States until 1856.

I was about to gild the lily.

For the next couple of days, I worked on connecting the Revolutionary War Nicholas Hoffmann with my great grandfather. Eventually, I crafted a story, complete with genealogical support, that the Revolutionary War Nicholas traveled BACK to his Germanic homeland after the war to raised a family — including my great grandfather. I concocted the explanation that by the late 1840s, my great grandfather became dissatisfied with the social upheaval in Europe and decided to immigrate to the United States (that much was true).

Well, it should be needless to say, my fifth grade teacher was having none of my story! It was just too far-fetched to even be given any modicum of consideration. I received an “F” for my genealogy project.

Creating the story to embellish the relic

It isn't just fifth graders who are guilty of “gilding the lily.” Collectors of antiques — especially military antiques — are susceptible to the powers of suggestion. That is why we need to make sure our research does not “start with a conclusion” and then work backwards.

Anyone can fall victim to the urge to connect the history to the facts. Military Trader recently published an article about a Colt double action revolver (see: “The Revolver that Found Me”).

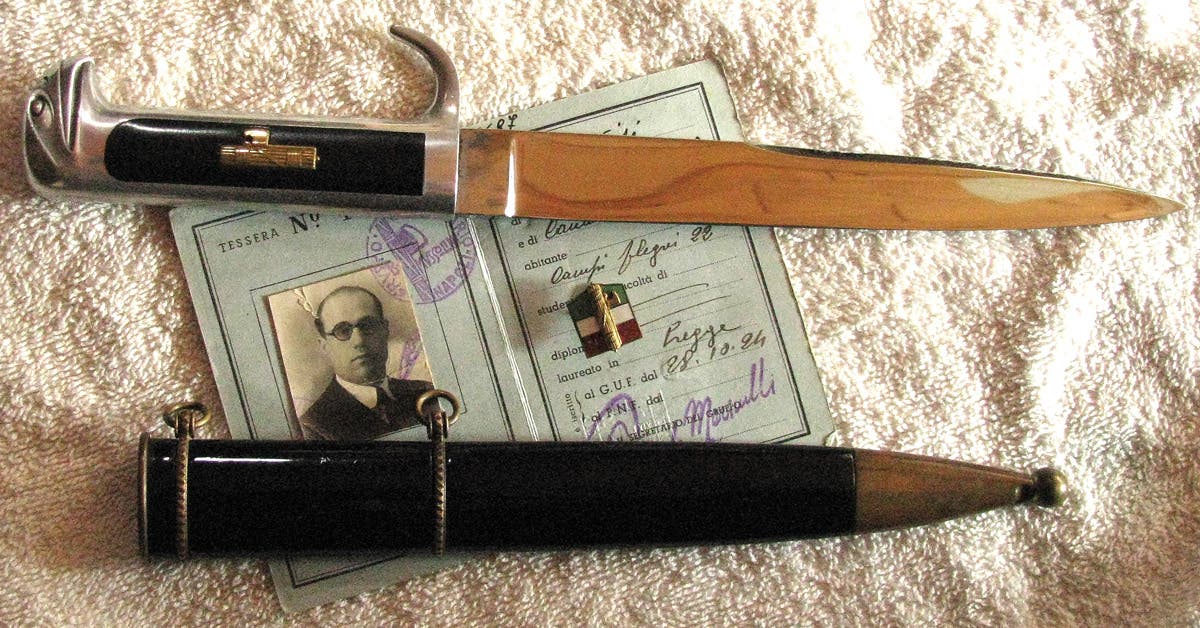

The author, a longtime collector and writer, found the revolver at a gun show. He discovered the initials “L.E.B.” stamped on the frame. Checking what he considered to be a tried-and-true listing of inspector markings, he concluded that the initials did not belong to any inspector, but rather, were those of the gun’s original owner.

He searched unit rosters from the era and finally concluded that the gun had belonged Major Lemuel E Boren, an officer in the Philippines Constabulary. What made the discovery even more fantastic was that the author specialized in items from the Constabulary. This revolver became an immediate treasure to add to his collection.

But there was a problem. While he trusted his list of inspectors, research had proliferated since it had been published decades ago.

A quick “Google search” of the initials “L.E.B.” coupled with “Colt Revolver” revealed that his weapon was not unique. In fact, according to Antique Arms Inc web site, the LEB-marked revolvers were refurbishments done under contract by Remington. Capt. Leroy E. Briggs was the Remington's inspector of these refurbished arms. Most, if not all, went to the US Navy.

This is from their web site: "As many of you know, most of these early 1894 Models were upgraded to the Model 1901. This one managed to escape all the modifications and improvements which means it never had a lanyard installed and still has all matching numbers including the barrel with the early 1884 and 1888 patent dates intact. These revolvers served in cavalry units in the American West, the Spanish American War, Philippines, and the Chinese Boxer Rebellion."

The info on the web site continued: "When the US entered WW1 in 1917, the Army contracted with Colt to have approx. 19,500 of its DA revolvers (Models 1892 through 1903) repaired and refinished. Unfortunately, Colt was too busy building 1911 Autos to perform extra work so the contract was awarded to Remington Arms-UMC which carried out the work at their Bridgeport plant in 1918."

Furthermore, in his 2004 book, A Study of Colt's New Army and Navy Pattern DA Revolvers 1889-1908, Robert Best points out that these revolvers were not upgraded, but were simply refinished and repaired, if necessary. In fact, Best documented that the Ordnance Dept. assigned Captain Leroy E. Briggs to inspect the work until August 1918.” Antique Arms Inc. added, “ If you look closely on the left side of the frame, you will see Captain Briggs' inspection mark, "LEB" just above the left grip panel."

Based strictly on the initials stamped on the revolver featured in the Military Trader article, the revolver had no association with Major Boren of the Philippine Constabulary. Regardless, the initials led the author to the premature conclusion that the weapon had a significant provenance. Unwittingly, he “gilded the lily.” (Note: This was not done nefariously. The author quickly amended his article with the new information in the hope that misidentification doesn’t follow the revolver.)

The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose

In the “Merchant of Venice,” William Shakespeare’s character, Antonio, warns Bassanio, “The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose,” declaring, “what a goodly outside falsehood hath!”

There are a few ways that relics are embellished. Recognizing them can stop you from succumbing to Antonio's warning.

One area to avoid is importing data that isn't there to support a conclusion. In the case of my attempt to adopt Revolutionary War veterans into my family pedigree, I “imported data” of a return trip to Europe by my adopted ancestors. The supporting evidence, however, didn't exist.

Another slip down the misinterpretation slope is failing to consider other interpretations. In the case of the MT author who incorrectly concluded the provenance of the revolver, he failed to “consider other interpretations” produced by current research. Unwittingly, he relied on what he believed to be accurate research, though it was more than thirty years old.

And finally, protect against confirmation bias by choosing bits of data that support the conclusion that you want to find. While a conclusion by confirmation bias is still backed by evidence, it will contain at least one illegitimate step by the selective use of data (that is, ignoring things that don't support your conclusion). In my case of genealogy, I ignored the fact that my family didn’t arrive in the United States until after the American Revolution.

While duplicitous intent doesn’t mark all faulty research, the results can, nevertheless, be devastating to the historical record. Therefore, when any of us are looking at a photo, studying a uniform, restoring a vehicle, or working with any other historical artifact or record, we have to remember that finding clues are not the same as reaching conclusions.

The point is, our historic artifacts, relics, and vehicles can't talk. They can't tell us their stories. But, they are building blocks for establishing a historic record. That is why it is so important that we use them appropriately and represent them with verifiable facts. In that way, we will truly...

Preserve the Memories,

John Adams-Graf

Editor, Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine

You may also enjoy:

*As an Amazon Associate, Military Trader / Military Vehicles earns from qualifying purchases.

John Adams-Graf ("JAG" to most) is the editor of Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine. He has been a military collector for his entire life. The son of a WWII veteran, his writings carry many lessons from the Greatest Generation. JAG has authored several books, including multiple editions of Warman's WWII Collectibles, Civil War Collectibles, and the Standard Catalog of Civil War Firearms. He is a passionate shooter, wood-splitter, kayaker, and WWI AEF Tank Corps collector.