From ‘His Majesty the King’

A look at the Imperial Service Badge from the British Territorial Force.

In 1905 the British Liberal Member of Parliament, Richard Burdon Haldane was appointed to the position of Secretary of State for War, a position he would hold until 1912. During his tenure he implemented a series of reforms within the British army, which became known as the ‘Haldane Reforms’. The changes he introduced would lead to Britain being better prepared for war when it came in 1914. One of his changes was the creation of the ‘Territorial Force’ which came about as a result of the Territorial Forces Act which had been passed by Parliament on August 2, 1907 and came into effect on April 1, 1908.

Britain had a long tradition of voluntary military units being raised to defend the country the country in time of war when the regular army was deployed on campaign. Haldane’s idea was to replace the Voluntary Force, which dated back to 1859, with the more modern Territorial Force, including the Yeomanry, mounted units of riders, some of which dated back to the 18th century. He encountered opinions from politicians who were divided over the exact role of the new Territorial Force. Haldane explained that it was not intended that the force should be ordered to serve overseas, but rather, in time of war, it would be responsible to protect the country while most of the Regular army was deployed overseas.

Haldane’s Territorial Force reforms created 14 divisions, each with three brigades, and 14 Yeomanry mounted brigades, with infantry battalions being integrated with regiments of the regular army, such as the three battalions which would be associated with the Northumberland Fusiliers. Further units of the Territorial Force would include artillery, engineers and signallers. It was to be a single force commanded by the War Office in London but administered by local County Territorial Associations. Unfortunately the force was not without its problems in terms of training, equipment and a year after its creation the strength of the Territorial Force stood at a level of around 268,000 men. The regular British army, which did not have conscription and relied on volunteer recruits to enlist, stood at around 250,000 men. In 1910 another change came with the introduction of the Imperial Service Obligation, under the terms of which members of Territorial Force battalions could agree to engage in overseas service.

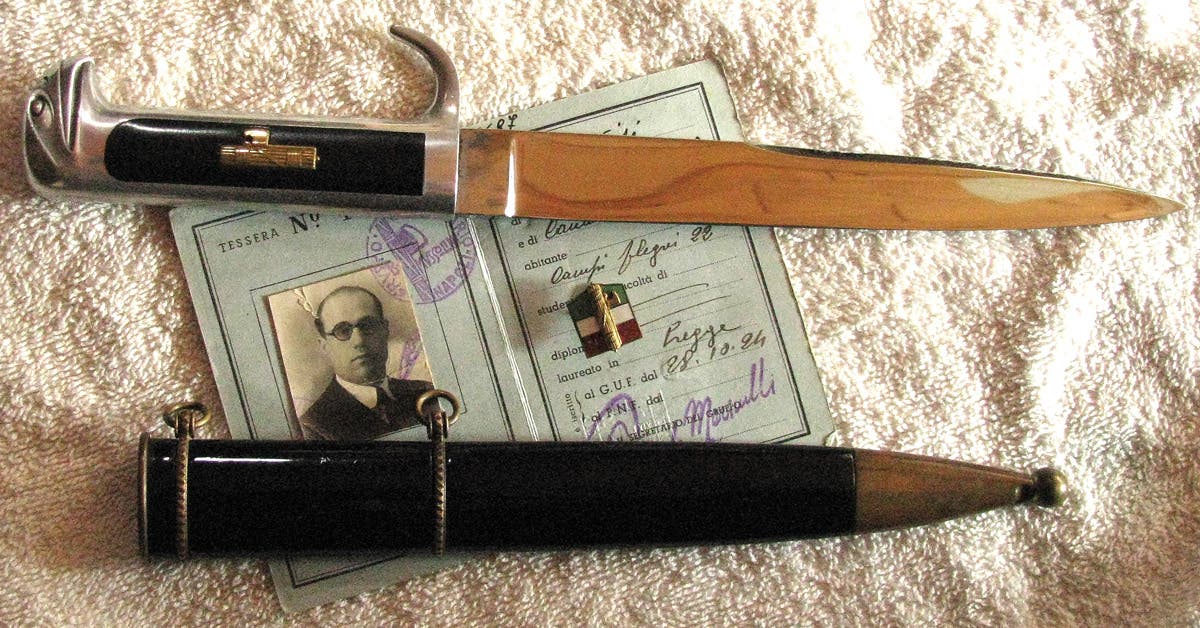

This was a voluntary agreement signed by officers, NCOs and men of the Territorial Force to show they were willing to serve overseas and agreed with conditions as laid out on Army Form E624, just like any formal contract between two parties. Details of the signatory, such as his name, rank at time of signing, service number and regiment were entered and the document counter-signed by the man’s Commanding Officer, dated and stamped. A copy of the form was attached to the man’s service papers and even when conscription was introduced in 1916 the documents remained on record.

In recognition of their commitment, all those who signed the agreement each received an official, silver-coloured badge bearing the legend ‘IMPERIAL SERVICE’ in capital letters. These badges marked them out as being ‘Imperial Service Men’ from the wording on the badge. These were men who had agreed to serve in any place outside the United Kingdom, as covered under provision of Section XIII (2) (a) of the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907. The awarding of the silver badge was covered specifically under ‘Army Order 3’, dated 1910, in which it was stated:

1) His Majesty the King has been graciously pleased to approve of a) A badge being worn on the right breast pocket of officers and men of the Territorial Force when in uniform who take the liability to serve outside the United Kingdom in time of national emergency…

2) (b) Each Territorial Force unit, 90 percent of whose serving members are under such liability, having that fact recorded in a suitable manner under its title in the Army List.

Even so, by 1913 only seven percent of members of the Territorial Force had signed the Imperial Service Obligation forms and the strength of the Territorial Force had fallen to 246,000 all ranks. When war was declared in August 1914, there was a reversal in opinion as many battalions in the Territorial Force, such as the London Scottish and Liverpool Scottish Regiments, volunteered to a man to serve overseas. It was they who would replace the losses in the first months of the war and make up numbers until recruits had been trained. Although awarded to indicate a man’s willingness to serve overseas, the badge was only worn whilst in Britain and very rarely, if ever, worn on service in either France of Belgium.

The badge was made of cupro-nickel, giving it the appearance of being made from silver, and known officially as the “Territorial Force Imperial Service Badge”. It has the form of a rectangular device, sometimes referred to as a “tablet”, measuring 10mm in height and 43mm in width. The top edge is surmounted by a Royal crown set in the middle which increases the overall height to 26.5mm, but, even so, it still remains a rather inconspicuous emblem. The reverse is usually plain, with the majority lacking any form of identification such as makers mark. Some were produced with the maker’s name on the reverse, such as ‘Lambourne & Co. Birmingham’, which manufactured buttons and badges, and these are sought after by collectors.

Unlike service or campaign medals of the day or the Silver War Badge, there is no means of identifying to whom the badge was awarded. There is no accurate account as to the number presented, rendering them virtually anonymous. The only way of identifying the owner is if it forms part of an important medal group, such as that to Corporal James McPhie, of the 416th (Edinburgh) Field Company, Royal Engineers (Territorial Force), who won one of the last Victoria Crosses of the war for his actions, and is today held by the Imperial War Museum in London, England. It was on Oct. 14, 1918 that McPhie single-handedly repaired a bridge under enemy fire to allow the passage of 1/2nd Battalion London Regiment, a Territorial Force battalion, across the river. Corporal McPhie was mortally wounded and was awarded the Victoria Cross. He would have had the Imperial Service Badge, but not worn it on service in France, and this is now part of the collection.

There are photographs showing men wearing their Imperial Service Badges, and if these are annotated with the man’s details he can be identified, but not his original badge. If taken in Britain, this usually dates such photographs to between 1910 and 1915, because the badges tended not to be worn after that date. Looking at a man’s service number also points to his being in a Territorial battalion and confirmation can be gleaned by the fact that most Territorial Force men had numbers below 10,000, until 1917 when the system was changed. For a collector wishing to build a display focusing on Territorial Battalions in WWI the inclusion of the badge will add to it. When the Territorial Force was renamed the Territorial Army in 1921, the last direct connection with the badge, with its history of only eleven years, was lost.

The badge is not particularly rare and an example can be obtained from a dealer either at a militaria fair or through an Online site specialising in militaria. Prices vary according to condition, but a badge in reasonable condition can be purchased for around $20. Some badges had finishes of low grade, and when compared to those of better quality the difference is immediately obvious. Damage usually occurs with the crown being bent or broken and the securing pin on the reverse has often been replaced. Likewise, the attaching points for the pin may have either replaced or re-soldered. There was a time when these small items were not considered of any value, but today collectors realise how important they are as an item to complete a section on the early part of WWI. There are replica versions now on the market, but an astute collector with experience will be able to spot those for what they are.