Finding Leo

Grandmother’s story leads to uncovering a hero’s record by Michael Staton Sitting on my feet, boosting myself to see the whole kitchen table,I reached to adjust one of my plastic…

Grandmother’s story leads to uncovering a hero’s record

by Michael Staton

Sitting on my feet, boosting myself to see the whole kitchen table,I reached to adjust one of my plastic soldiers into the correct position. My grandmother’s words echoed stories I already had heard many times before, even at my young age. It was during the late 1970s when my grandmother had come to stay with us. On this particular evening, it was my turn to sit with her and keep her company while I multi-tasked between commanding my little green men on the oak battlefield and listening to her stories. After picking up one of my riflemen and studying the toy, she began to retell my favorite story

“My brother Leo had toy soldiers. Of course they were lead back when we were young,” she began. “He was one of the nicest young men you would ever want to meet. He and I got along so well. He was the big brother who looked out for me.”

Her eyes brightened as the memory made her smile, “He was drafted into the Army during World War One. We called it the ‘Great War’ back then.” She continued, “He volunteered to be in the Tank Corps. I guess he wanted to do his part or he thought it was going to be an adventure.” After a brief pause, perhaps to recall the features of her brother’s face, she continued, “We had a big send off before he left to go over there.”

Then her eyes sunk. She quietly admitted, “He came to me in a dream after that. I remember thinking, ‘He can’t be here – he is in France!’ He told me, ‘Tell mom and pop that I’ll be all right.’” My grandmother’s voice became very solemn at this point, “I didn’t know what my brother meant, but two days later, a boy on a bicycle came to the house and dropped off a telegram.” A tear streamed down her wrinkled cheek, “Leo was dead.”

Grandmother went on, “We didn’t know what had happened until a few of his buddies came by my pop’s grocery store after the war. They said Leo had been shot in the eye before their tank was put out of action. They all got out of the tank and made their way back to friendly territory, but Leo didn’t make it. One of them left my pop some money he said he owed Leo from a poker game. Leo didn’t gamble. I think they all took up a collection to give to my folks.”

FILLING IN THE PIECES

I am not sure why, but about 10 years ago, I was thinking of my grandmother’s story about her brother. I decided I wanted to learn some more details of the man whom I had always considered to be a hero.

My first effort was to contact the Military Personnel Department in St. Louis. This is where I learned that many records were lost in a fire in 1973 – including Leo’s. After a few exchanges, however, I received copies of documents pertaining to the shipping of Leo’s body back to the United States in 1921.

According to these documents, he was in the U.S. 2nd Tank Brigade (the parent organization of the 301stTank Bn.) attached to the 4th Tank Brigade of the British Expeditionary Force. They also identified the United States cemetery in which he was buried.

A visit to the Mother of God Cemetery in Covington, Kentucky revealed no tombstone –and no gravesite. Unable to find any more information, I put the project on the back burner.

In 2014, I renewed my effort, this time exploring what I could find on the internet. Discovering that his unit was the 301st Tank Battalion, I learned as much as I could on the unit.

Leo had been in Company C and was killed in action while attacking the Hindenburg Line on September 29, 1918. I found a list of all the 301st tank commanders and the registration numbers of all the tanks that the Battalion used in the battle,but I was not able to determine in which one Leo had served.

DID NOT DIE IN VAIN

Finally, I discovered a short article that explained Leo’s final moments in combat. It was published in Kentucky Post, onJanuary 30, 1919, and began:

“Comrades Honor Courage of Covington Hero.”

“Near the little village of St. Emilie, France, in a tiny graveyard where lie the bodies of hundreds of British and American heroes, is a spot which belongs distinctly to Covington.

“It is the spot where Leo Rauf, 502 W. Sixth St. Covington, was buried reverently by his comrades after he gave his life in one of the hardest battles of the world war.

“Lieutenant Robert O. Vernon, commander of the American tank crew of which the Covington boy was a member, tells the story of the battle in a letter to Rauf’s parents.”

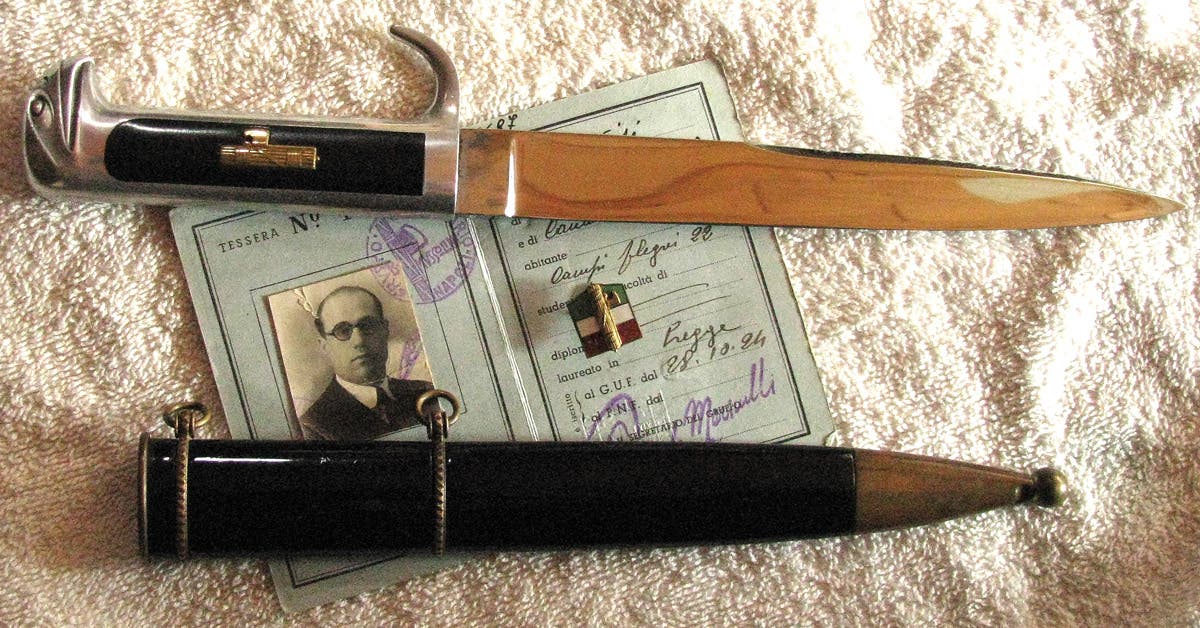

Vernon commanded the British Mark V tank no. 9376. With Rauf manning the 6-lb gun on the “composite” tank (meaning that the main armament on one side was a machine gun and on the other, a 6-lb naval cannon), the massive rhomboid vehicle had progressed quite far during the September 29, 1918, attack before it was immobilized in a trench. The article in Kentucky newspaper explained the events in a letter written by Lt. Vernon:

“I am mighty proud of him [Leo Rauf]. He did not die in vain,” Vernon wrote.

“Rauf, in the memory of his superior officer, will remain one of the real heroes of the war,” Vernon related. “one of the men who scorned pain and danger to stamp autocracy from the face of the earth.

“For, with one eye shot out, Rauf loaded the six-pounder with which his tank was armed as fast as the lieutenant fired the weapon. He made no complaint, but fought his share of the fight to die with the words, ‘Well, I’m glad I got some of the Jerrys before they got me!’

“The lifting of censorship at this time permits me to inform you of Leo, who was a corporal of my crew. It is no pleasant task for me to inform you of his death, but thought you might care to know how he met his death. He was one of the most cool headed men in the tank and didn’t make even a whimper when he knew he could not live.”

They Broke The Line

Vernon’s letter continued with a description of Rauf’s unit. “The battalion went into action for the first time between Cambrai and St. Quentin on September 29, near the small towns of Le Catelet and Bellincourt. At Le Catelet, the St. Quentin Canal, which forms an almost impassable barrier in front of the Hindenburg Line, passes through a tunnel more than 6,060 yards long. To break the Hindenburg Line the British saw that this tunnel would have to be crossed.

“The Germans knew it also. Consequently they had it strongly fortified. Two American divisions, the Thirtieth and the Twenty Seventh, with the American and some British tanks were given the job of taking the tunnel and breaking the line. It is needless to say they did.

“Our tank got through the first line with only two wounded, Leo and another Corporal. A machine bullet had wounded Leo in the right eye and ear, but in spite of that he loaded the six-pounder while I fired. We had one breathing spell in which we gave him a drink and washed his face.”

Tank Is Set Afire

Vernon even described the fate of No. 9376, the tank in which my Great uncle served. “In coming back we ran into some more Jerrys, and the tank was set on fire. The only thing to do was evacuate,” the Lieutenant wrote.

“The machine guns and two snipers were firing at us. However, no one was hit. I examined Leo’s eye again and saw it was gone. We rested under the tank for a while but had to leave because of the fire.

“We rushed from one shell hole to another for more than a mile back toward our lines without being hit by rifle bullets. However, when we reached the road the Germans began shelling us heavily. One shell broke one man’s leg twice below the knee, wounded another and severely wounded Leo.”

BURIED IN A FRENCH GRAVEYARD

Lt. Vernon’s letter also answered my questions about what became of Leo’s body after he was killed. Vernon wrote, “Heis buried near the small village of St. Emilie in a grave yard with a lot of American and British soldiers. I judge it is about 3½ miles west of Le Catelet and Bellicourt.”

He concluded the letter that he sent first to Leo’s parents, “I only mention the fight because I thought you would like to know what kind of a ‘show’ Leo was in. I am mighty proud of him. He did not die in vain. The ground taken on September 29 was considered the hardest place on the Hindenburg Line. No fight afterward even could compare.”

With the exception of his 4-year hitch in the US Army as a light wheeled vehicle mechanic, Michael Staton is a lifelong resident of New Bremen, Ohio. Michael is a full time CNC machinist and a part-time author/historian. He is the author of The Fighting Bob, a history of his father’s WWII service on the USS Evans. Michael collects WWII Pacific Theater items and has recently purchased a 1943 Willys MB “project.”