It’s Memorial Day…What do your remember?

An old movie asked the question: “Today is Memorial Day. What am I supposed to remember.” For me, I remember the WWII veterans who used to gather every morning at our store to drink coffee together. They never knew the impact their daily ritual had on me.

The Minnesota-made movie, “Memorial Day,” premiered to audiences around the United States several years ago. The story revolved around a grandson and his grandfather, a WWII veteran coping with the onset of Alzheimer’s. The inquisitive youth had discovered a trunk of souvenirs and asks his grandpa to explain each relic. First refusing, the old man relents when his grandson asks, “Today is Memorial Day…What am I supposed to remember?”

GROWING UP IN THE SHADOWS OF WWII VETERANS

The movie was met with mixed reviews, but it has stuck in my memory. Of course, I have a soft spot for stories about father-son relationships, especially if the parent is a veteran. I suspect this is something I have in common with most of you, in fact.

I was fortunate to grow up in the shadow of WWII veterans. I was a young boy at the time most of them were allowing themselves to recall their service. Sitting on the checkout counter of our family grocery store, I started many days listening to my Dad and his buddies swap tales. They never spoke directly to me, but I knew they were speaking for me. I absorbed each story as I watched the men—most in their 50s—relive their youthful, military exploits. Though I remained silent (I knew my place with my elders), I listened intently—they were passing something to me that I was supposed to protect.

Dad’s best buddy before the war was Gale Buxengard. After their service, they both eventually returned to their hometown, Caledonia, Minnesota. Dad bought an old grocery store, and Gale found employment in the Post Office. Whereas Dad remained in the States during the War, Gale went to Europe. Gale’s stories of speeding across Europe in a Jeep as he tried to keep up with General Patton kept me riveted.

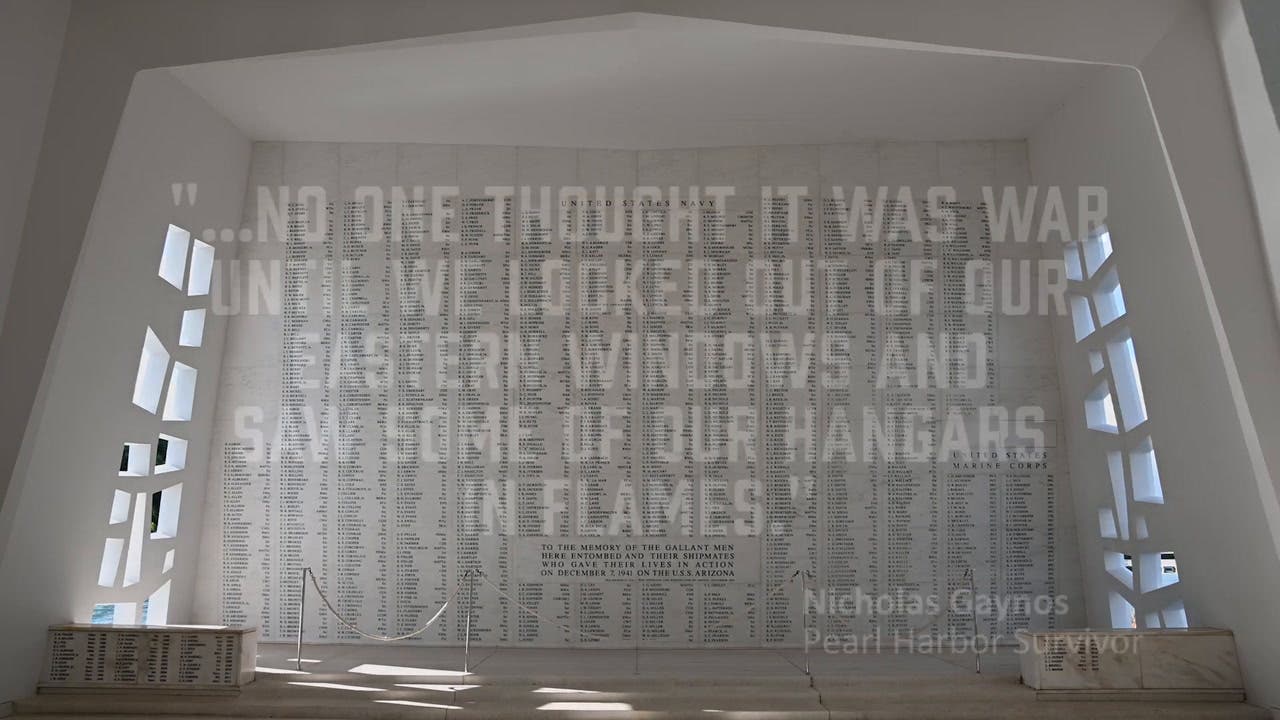

Ross Johnson owned the Coast to Coast store across the street. His morning began at our store, as well. Sharing a cup of coffee, Ross would talk about his time in the Pacific as a member of the U.S. Navy.

Just down the block from Ross’ store, Earl Wagner had his insurance business. Earl, too, stopped in for the morning coffee and conversation. He would interject his tales of his service in the European Theater.

Vic Palen lived in the house next to ours. Vic grew up in the house just as my Dad grew up in the three-story Victorian where we lived. The two had been buddies since they were old enough to run into the flower gardens that separated the two homes. Both shared a passion for photography.

After high school, Vic went to work for his photographer father, Frank Palen, and Dad found employment in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, as a technical photographer for Trane Company. After the War, they raised their families in the same homes in which they were raised. Vic’s children and my brothers and sister all became close friends. Sharing stories between kids and adults was a daily occurrence. Vic welcomed the opportunity to tell me his stories of taking high-altitude photographs over Europe to assist in the bombing campaign against the Germans.

It was a rare morning when Ralph Eikens would join the crew at our store. Though Ralph operated the Hardware Hank just down the block from the store, he probably didn’t feel compelled to come over for the morning kaffeeklatsch as he was also our next-door neighbor in addition to being our bookkeeper and being married to Dad’s first cousin. Our two families spent countless hours together—holidays, summer cookouts, pontoon excursions on the Mississippi and just standing in the yard chatting. Of all of Dad’s wartime buddies, Ralph had the most obvious scars of war.

Ralph had been a combat medic in the Pacific Theater. During the Battle of Iwo Jima, he was carrying the front of stretcher loaded with a wounded Marine when a mortar round hit behind him. The man carrying the rear of the stretcher disappeared in the blast as the litter and the wounded Marine sailed over Ralph’s head as shrapnel peppered his legs and back. In the 30 or so years since suffering the wounds, Ralph still limped and dealt with crippling arthritis.

A DIFFERENT TIME, INDEED

The early 1970s presented a conundrum to a young kid who liked to listen to the war stories of his dad’s buddies. The Vietnam War was separating the nation along lines clearly drawn between the support of veterans and decrying the conflict in Vietnam.

On one hand, I listened with awe to the WWII veterans tell their tales, but on the other, I didn’t know how to talk to the young soldiers returning to Caledonia from Southeast Asia.

After Vic’s oldest son returned from Vietnam, he spent a lot of time walking. I watched him pass by our house nearly every day, wearing an old, olive drab jungle jacket. I wanted to ask him about the patches on the faded jacket, hoping maybe he would tell me some thrilling tale of combat—but I just couldn’t find the courage to approach him. Did he even remember me? I was just a 10-year-old kid and here walked a young man who had been across the world fighting a war that appeared in the nightly news. I don’t think he even saw me as he walked past me every day. I never did learn his story.

My parents coached me before Ralph’s son returned home from Vietnam. He had been a Marine Scout who led several patrols. During not one, but two patrols, enemy soldiers ambushed him and his squad. Between the two ambushes and several other engagements, he lost most of his squad—either dead or wounded so severely as not to return to his command.

My folks knew I would ask him to tell me all of his war stories, so they preemptively chastised me, “Don’t talk to him about the War.”

One day shortly after he came home, he joined me at the basketball hoop in the driveway between our houses. Remembering my parent’s admonition, I gingerly asked, “You wanna take me hunting this fall?” It seemed like a safe question. Before he went to Southeast Asia, he and my brothers often hunted the woods surrounding our little town.

He didn't look at me before he answered. I assumed he was concentrating on his next shot at the hoop.

“No John,” he finally said as he let the ball sail toward the net, “I can’t go hunting anymore.”

I assumed he had broken some law that forbid him from shooting Minnesota squirrels.

Not because of the advice my parents had given, but simply because I was a little kid, I didn’t say anything. I picked up the ball and threw it at the hoop—maybe just a bit angrily to mask my disappointment. It wasn’t until many years later did I understand his response had nothing to do with the squirrels, our youthful hunting trips, or me.

This Memorial Day, I know what I will remember: Dad, Ralph, Ross, Earl, Vic, Gale, their sons, and so many others who carry the burden of war with them through their entire lives.

Preserve THEIR Memories,

John Adams-Graf

Editor, Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine

You may also enjoy

*As an Amazon Associate, Military Trader / Military Vehicles earns from qualifying purchases.

John Adams-Graf ("JAG" to most) is the editor of Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine. He has been a military collector for his entire life. The son of a WWII veteran, his writings carry many lessons from the Greatest Generation. JAG has authored several books, including multiple editions of Warman's WWII Collectibles, Civil War Collectibles, and the Standard Catalog of Civil War Firearms. He is a passionate shooter, wood-splitter, kayaker, and WWI AEF Tank Corps collector.