WHEN EVERYTHING “GOES HIGH”

“Honestly, what I think shocks me most about the auction is how high EVERYTHING went,” a friend wrote about a recent militaria sale. “I know of at least five other…

“Honestly, what I think shocks me most about the auction is how high EVERYTHING went,” a friend wrote about a recent militaria sale. “I know of at least five other serious collectors who were bidding on things, and not one won anything. That says there are some deep-pocket collectors out there who we don't know,” he added before concluding, “I've long suspected this. There is another level of collectors who aren't the military show types.”

As I read his missive on a recent sale, I had to agree that there is probably a “dark” group of “high rollers” who exist within our hobby. However, I wonder if there isn’t something more quantifiable at play.

QUALITY SELLS

One thing is constant in most 20th and 21st-century collecting hobbies: Quality always sells. It doesn’t matter what the economy is doing or what is happening in the geopolitical arenas, high-quality antique collectibles always have a market.

If you don’t believe me, look at hobbies that have declined significantly since the end of the Cold War. Take stamps, for example. While you can’t hope to find a buyer for your H.E. Harris album full of soaked-off cancels, if you offer up your 1918 24-cent “inverted Jenny” postage stamp for sale, you can expect to find many willing buyers at the $500,000+ level (the last public sale of one of these “errors” commanded a price of $817,000). According to Stanley Gibbons' GB250 Stamp Index, rare postage stamps offer better returns than property, gold, and the broad stock market.

And while most of us believed we were creating something valuable as we pressed Lincoln pennies into blue, tri-fold albums when we were younger, the reality is, a “full album” might sell for around $20. But that isn’t to say coin collecting is “dead” or “dying.” Coin collecting is big business, and the rarest, most covetable specimens fetch unbelievable prices when they come on the market. For example, a US 1833 five-dollar “capped head left / half eagle” recently sold for $1,351,00. Last year, an 1894 “S Barber” dime sold for just shy of two million, closing at $1,997,500. That ain’t pocket change!

Perhaps a group that is harder to relate to for most militaria collectors are the “game card collectors.” Regardless, in terms of "valuable," the take-away is the same. Consider the sale of a Pokemon card just this past November. Dubbed “the world’s most valuable card,” a card given to winners of a 1998 Corocoro Comic Illustration contest sold at a Beverly Hills auction for more than $50,000. It was one of only 39 copies ever made. Its rarity — and desirability — catapulted it to the status of "most valuable card."

Okay, if you still don’t believe that a high-end market exists in all collectibles, let’s look at the poster child of bad investments: Beanie Babies. Remember when everyone was convinced that Beanie Babies, first introduced in 1993, would be worth tons of money one day? Ultimately, the reality that most Beanie collectors face is that their stuffed toys aren’t worth the fabric surrounding their beanie innards. Regardless, an internet search turns out dozens of stories of “Princess the Bear” selling for $500,000 or other equally outrageous claims. Dig a little deeper, and you will learn that those stories were fabricated. The truth about Beanie Babies is that they aren’t worth diddly — even the “rare” ones rarely sell for more than $100.

DID I GET IT WRONG?

Based on the Beanie Baby reality, my earlier premise that “all collectibles” have a high-end market needs to be adjusted. The difference between militaria, stamps, coins, or even Pokemon cards and Beanie Babies, Franklin Mint figures, or commemorative quarters, is that the first group represents items that were manufactured with a tangible utility: Fighting wars, sending mail, purchasing commodities, or even playing a game. Items in the second group were manufactured for one purpose: To sell to “collectors.”

So, I need to adjust my premise: High-end antique collectibles always have a market. This is because there are some simple economic rules at play.

“Economic rules?” I bit my tongue when I typed that one. I absolutely hated economics when I was in college. Despite nearly topping my list of “Most-skipped Classes” (Philosophy 101 tops that list), I seem to draw on the lessons I took away from my Economics class. One of the most important rules I wrote in my notebook during one of the few classes I actually attended was, "When a nation is politically uncertain, people will invest in tangibles: Wine, gold, guns, art, whatever..."

And while many complain today about a soft economy and a slow market, “Untitled,” a Basquiat painting from 1982, just sold for $110.5 last month. Earlier this year, a Ferrari 335 Sport sold for $35.7 million. And while not the highest price ever paid for a firearm, Rock Island Auction recently sold a Model 1886 Winchester for $1.26 million. Clearly, there are people with plenty of money to purchase quality antique collectibles.

So why don’t we see those sort of prices in the militaria hobby? Well, it can be argued that we do see those kinds of prices. That 1.26 million Winchester, for example, was presented to U.S. Army Captain Henry Ware Lawton, the man who captured Apache leader Geronimo. Whereas I would have had to drop out of the bidding around the $3,000 mark, I would happily push all of my militaria out of the way to hang that trophy on my wall!

I think the Winchester qualifies as “mega-cool militaria.”

Back in 2011, Spink & Son sold a WWII Victoria Cross awarded posthumously to Private Edward Kenna of the Australian 2/4th Battalion who exposed himself to the risk of getting killed just to take out a Japanese machine gun position during a battle near Wewak, New Guinea in 1945. Bidding ended at $550,000. That’s a righteous price for any piece of “militaria.”

Similarly, but crossing over to the car collector’s market, Hitler’s Mercedes-Benz 770K sold to a Russian collector for a reported $10 million. It wasn’t a Sherman Tank (last recorded sale for one of those was around $446,000), but it still falls into the realm of “military vehicles.”

So, you see, there is, indeed, a level of militaria collecting that is beyond what we see at shows, advertised in magazines, or offered on internet sites. The grim reality is, most of us — despite saying we have “rare” or “one-of-a-kind” items in our collections – really don’t have items on that level.

Remember, “Rare” does not mean “Valuable.” Just because only a few examples of something exist, that doesn’t change it into a money-catcher. To be “Valuable,” an object has to be “Rare” PLUS “Desirable.” A Ferrari GTO is just that: Rare and desirable. An 1840s Fisk zinc-lined coffin may be rare, it just isn’t all that desirable (enough to drive it to the $50K or above level).

And finally, there is something intangible at play here, but I haven’t quite figured out how to convey it. However, having attended auctions where cars or firearms sell for millions, there is something that clearly separates the million-dollar buyers from the sellers at most militaria shows.

There is a familiar feeling in most militaria shows—a camaraderie that most veterans and non-veteran collectors recognize. Military service, for the most part, has been fulfilled by the common man and woman. They served together through strenuous conditions, forming bonds to each other and their service that has lasted long beyond their service.

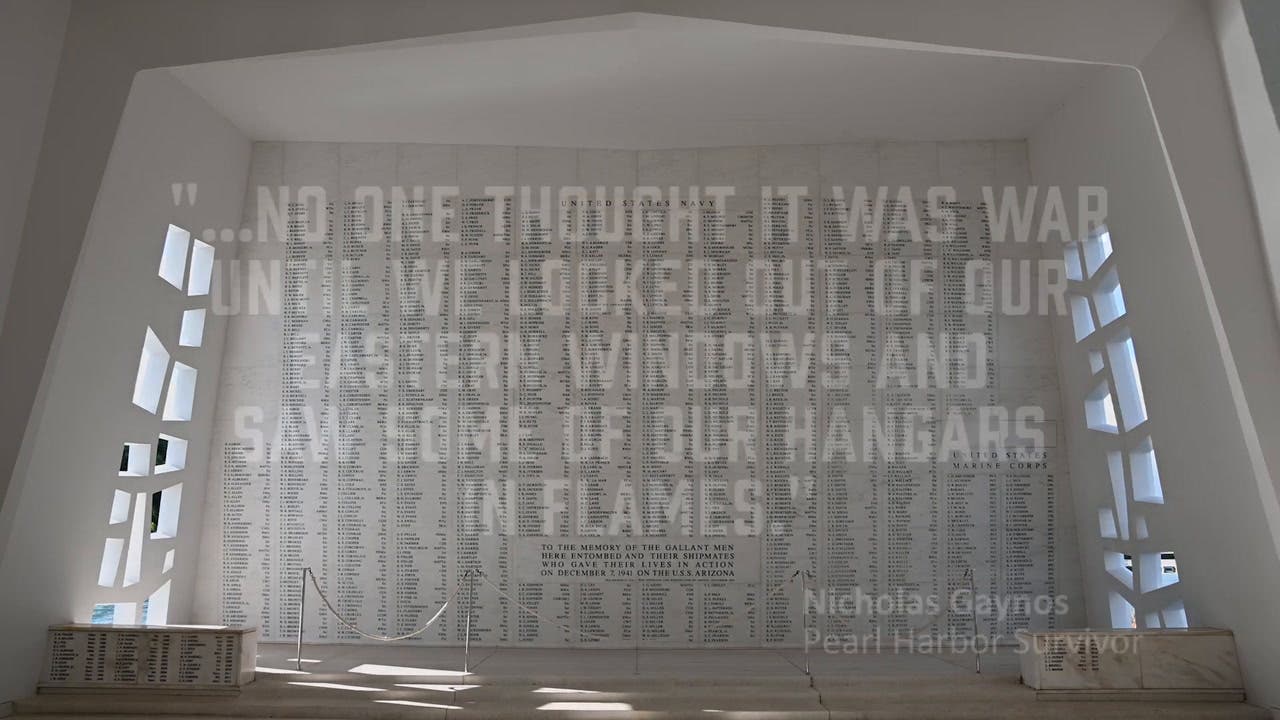

While our tables or booths at shows might be filled with helmets, vehicle parts, accouterments, medals, or whatever small trinkets that recall the service of military men and women, our commitment to the hobby is embedded in preserving the memory of that service — not protecting our wealth from market fluctuations. Most who collect militaria — whether they spend $10, $100, $1,000 or $100,000 on items— don’t do it for the potential monetary gain, but out of a historical curiosity and a desire to perpetuate our heritage.

Preserve the Memories

John Adams-Graf, editor

Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine

John Adams-Graf ("JAG" to most) is the editor of Military Trader and Military Vehicles Magazine. He has been a military collector for his entire life. The son of a WWII veteran, his writings carry many lessons from the Greatest Generation. JAG has authored several books, including multiple editions of Warman's WWII Collectibles, Civil War Collectibles, and the Standard Catalog of Civil War Firearms. He is a passionate shooter, wood-splitter, kayaker, and WWI AEF Tank Corps collector.